This is the second part of what I plan to be a long series concerned the area of the Dingle, Liverpool. This part deals with the area’s earliest history, up to the end of the 18th century.

Introduction

Since 2012, when I started this website about Toxteth Park, I have put off covering the original Dingle area. The reason for my reluctance was that it had covered many times before. I promised myself that I would only cover it if I could considerably add to the story. I hope you agree I have. I have intentionally avoided attempts at providing full biographies of the people in this and future posts, this post is long enough with attempting that. Instead I’ll add links along the way.

The story of the Dingle and it’s occupants (the Yates family, William Roscoe and James and John Cropper) have been so carefully edited since the 19th century that it almost resembles a fairy story (complete with a supernatural water nymph). One thing is for certain, the Dingle was a place of remarkable natural beauty. This was first enhanced by the hand of man, only to be destroyed by it a century later.

A little further on you arrive at one of the sweetest spots I ever met with in the course of all my travels. It is called “the Dingle,” and is a perfect little Paradise. When once you have entered it, you lose all idea and remembrance that you are within a few minutes walk of one ‘of the most noisy and bustling towns in England. You become so delighted and engrossed by what is immediately around you, that you forget the world beyond, with all its anxieties, cares, and troubles. As you advance through the romantic glen, you suddenly come upon the banks of the Mersey. The view at this point is in my opinion unrivaled.

Liverpool Telegraph – Wednesday 04 October 1837

Why is it called ‘the’ Dingle?

Although the area is also known as just ‘Dingle’, the place often has ‘the’ preceding it. This is a lot easier to explain than why we Scousers call ASDA ‘the ASDA’.

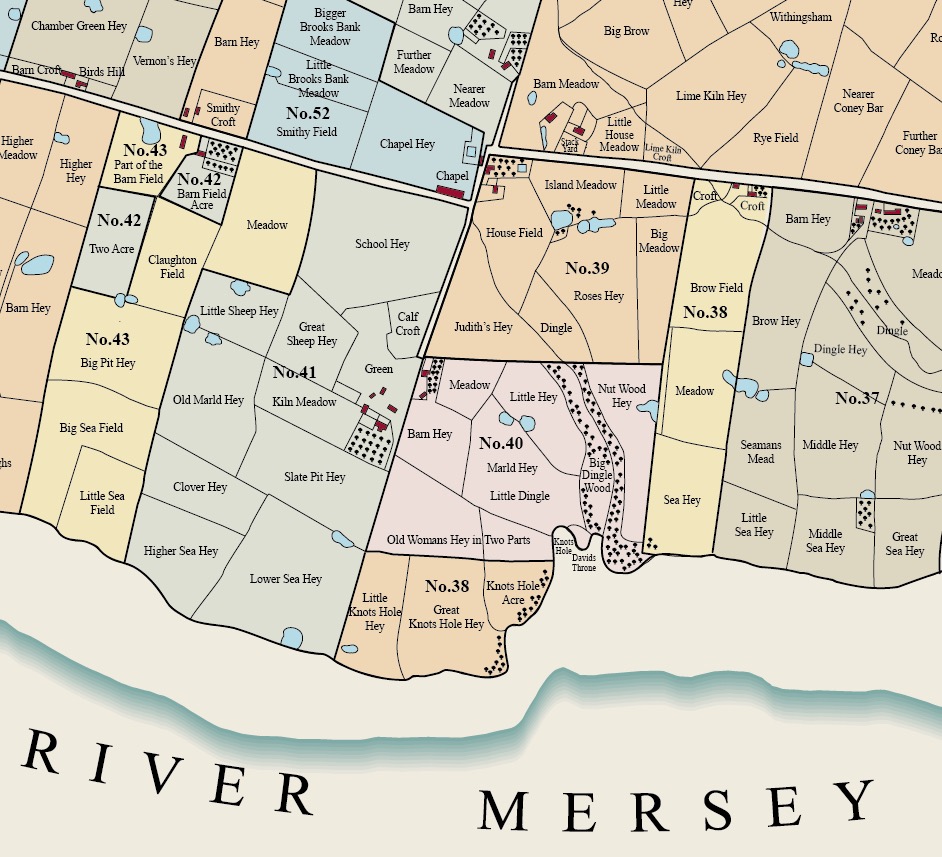

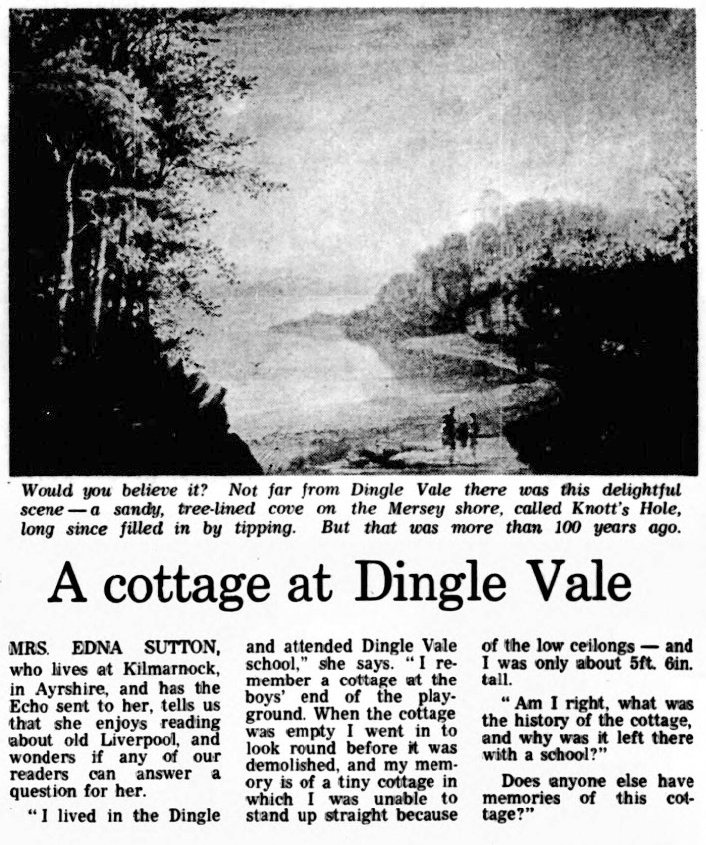

The Dingle was so-called because it was originally named after a geographical feature; the ‘wooded valley‘ that once lined the path of a stream down to the Mersey. This stream passed in front of the corner of Park Road where the Ancient chapel is, through the land that later became the Turner Home, and finally reached the Mersey near a place named Knott’s Hole. I have plotted the course of the stream below, the location of Knott’s Hole was not clear so I have added an arrow. I have also coloured the Ancient Chapel of Toxteth red.

Around the year 1790, one of Liverpool’s most famous sons, William Roscoe wrote a poem about the stream, which by that time had dried up. I covered this poem, and the statues inspired by it in the first part of this series. But Roscoe wasn’t the only person to be inspired by the area, other poems were written and several descriptions appeared in print that can be found elsewhere on my website.

The original Dingle was outside of what most people consider to be the Dingle today. ‘the romantic glen’ was south of Dingle Vale, its eastern border was Aigburth Road. The modern perception of the Dingle area is more recent than you may have thought.

See Miscellaneous notes at the end of the post.

Old images of the Dingle

Here are a selection of images to get us going. We’ll begin at the glen of the Dingle and follow it to the shore, at Knott’s Hole and Dingle beach. To assist I have marked the areas on this map.

The first photograph is the glen of the Dingle, this was the wooded vale that led to the Mersey. This is the bed of what would originally been a powerful stream. Note the children sitting on the fallen tree.

To stray unseen in Dingle Vale,

And rest in rose and woodbine bower,

While fragrant sweets float on the gale

From many a little pencil’d flower.To watch the moonbeam’s flickering play,

Poem about the Dingle belonging to Mr Yates, unkown author, 1824

O’er Mersey’s calm and silvery flood;

While soft is heard the dashing spray

Slow murmuring thro’ the echoing wood.

I have colourized that photo below. The landscape was not dissimilar to the grounds of Otterspool, that was also the bed of one of Toxteth Park’s ancient streams.

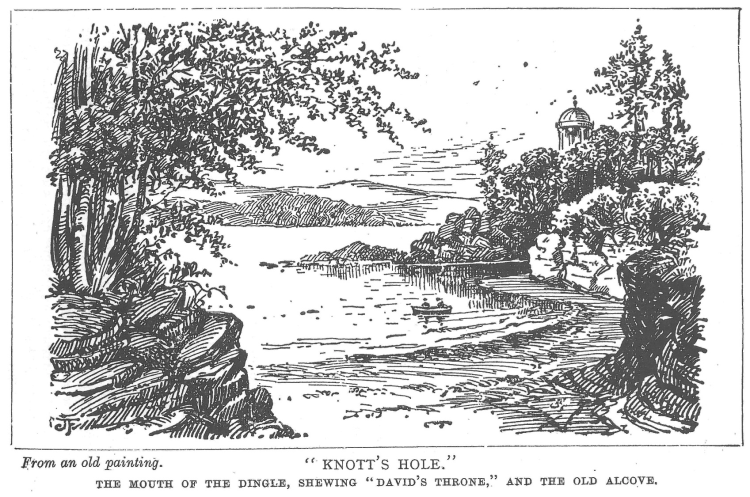

This photograph shows the end of the Dingle where it reached the Mersey. A fence blocks access to the beach, below this was a stone wall. The high ground in the foreground is ‘David’s Throne’. This was a pointed outcrop, on the other side of this was Knott’s Hole.

Here, too, I’ve seen the fair stream poured

Poem about the Dingle belonging to Mr Yates, unkown author, 1824

From rocky fissures bold and free;

Say was the Naiad e’er allured,

By floods more fair ‘neath shrub and tree?

This view had hardly changed in 100 years, here it is in 1800. This illustration accompanied the first publication of William Roscoe’s poem:

Here is the beach of the Dingle as seen from the shore. Note the stone wall, this was built to halt coastal erosion. Note also the little footpath winding through the high bank of trees:

This wonderfully clear photo below is viewed from the shore, here is the Dingle in the centre with David’s Throne on the left. The high wall on the right marks the beginning of the estate near to St Michael’s Hamlet that included the Priory.

Here is David’s Throne viewed from the small beach at Knott’s Hole, a group of bathers can be seen:

The illustration below dates from 1907, but it was copied from an older painting. It’s entitled Knott’s Hole, but actually appears to show the Dingle beach in the foreground, David’s Throne in the middle (the white rocks), and beyond that is an area called Dingle Bank. The furthest tip of this was known as Dingle Point. Knott’s Hole would actually be out of view, behind David’s Throne. The cupola on the top of Dingle Bank housed the statue of ‘the Lady of the Dingle’ that was a tribute to Roscoe’s poem.

Finally, here is Dingle Point, with its flag mast.

Knott’s Hole and the Dingle beach virtually disappeared when they were filled with waste in the early 20th century after industry took over the area. Part of the rocks of Knott’s Hole still survive and can be seen behind the trees at the roundabout of Riverside Drive and Promenade Gardens. I’ll cover the later period in the next installment.

Earliest records of the Dingle area

The history of the Dingle is bound to that of Toxteth Park. I’ve coloured the Dingle on this 1847 Tithe map below, it was virtually in the middle of the land bordering the Mersey.

A quick Toxteth Park recap

Toxteth Park had been a Royal Hunting ground from 1207. Toxteth was bounded on one side by the Mersey that was fed by four streams that ran though the park. Toxteth was taken by King John when he issued Liverpool with its first charter. The king enlarged it with an area called Esmedune = Smithdown. His men then promptly moved out all of the residents of Toxteth to his new town of Liverpool. The crown now had a hunting ground that covered a large area of modern south Liverpool, as they did across the country.

It then became a private estate owned by the Stanley family until the 1580s (of Knowsley Hall) and then sold to the Molyneux family (of Croxteth Hall). At this stage in history the status of the park changed, farmers, millers, fishermen and craftsmen were now encouraged to lease plots of land there. Many of these settlers were Puritans, and these people put the Dingle on the map.

Puritan settlers

Until the late 1580s, the number of occupants of Toxteth Park had changed little since the 13th century evictions. This all changed with the arrival of pioneer farmers and skilled craftsmen. Puritan by faith, that were encouraged to make new lives in the recently disparked area. Historians have speculated on the reasons why the Catholic Molyneux would encourage the Puritans to settle on his land. One theory given is that being a Catholic recusant made him sympathetic to their cause. In 1893, Edward Baines suggested that Molyneux would rather have his lands ‘in the hands of Nonconformists that in those of the dominant and persecuting church.’

I believe this was not the case. Instead, Molyneux wouldn’t have cared who leased his land as long as he was making money from it. The only reason that Puritans settled in his park was because the people that handled the transactions were Puritan themselves. Furthermore, it wasn’t Molyneux who had appointed these Puritan agents, Stanley did. But once the sale went through, Molyneux kept them on.

The date for their arrival is often given as the 1590s. But on my other (collaborative) website Bygone Liverpool, that date is pushed back to 1586. This was with a Puritan named William Foxe. 1586 was the same year that Lord (William) Stanley appointed two men (Edmund Smolte of Lathom and the Puritan Edward Aspinwall) to handle the sale of his estate. In 1604 Smolte and Aspinwall then acted as (estate) agents to the new owner, Richard Molyneux of Sefton. A report was made in May 1604 that detailed the estate of Toxteth Park (Tocksteth) and Esmedune (Smethdon – Smithdown) at that time.

24 messuages*, 10 cottages, 2 mills, 30 gardens, 20 orchards, 700 acres of land, 60 ac. meadow, 400 ac. pasture, 600 ac. heath and furse†, 300 ac. moss‡, in Tocksteth and Smethdon.

Molyneux muniments. Liverpool Record Office, transcribed from a collection deposited in the Lancashire County Record Office

* Dwelling house with outbuildings and land assigned to its use

† Same as gorse, a wild bush with sharp thorns and small, yellow flowers

‡ A boggy area located at the north east corner of Toxteth park used for collecting peat, the Moss Lake was the town of Liverpool’s source for fresh water. You can read about the Moss Lake in another of my posts here.

The landscape the Puritans inhabited

The term disparked relates to the status of the area being changed from being a private park into leased farm land and residences, i.e. ‘converted to husbandry’. It doesn’t refer to the forest being cut down. That process began four centuries earlier when Toxteth oaks were used to build Flint Castle in the 13th century. The majority of the forest had been used for centuries to build the town of Liverpool and its ships.

But a considerable amount of forest must have remained after the Puritans came here. Royalist-suppporting Lord Molyneux had helped Prince Rupert lay siege on Parliament-supporting Liverpool during the English Civil War (1642-1651). Afterwards, the Corporation forced him pay reparations. This included felling 500 tonnes of his Toxteth trees to help rebuild Liverpool. Molyneux also used his oaks for Croxteth Hall (probably during modifications in 1702). But by the mid 18th century, local timber was so scarce that some (slave) merchants were getting their ships built in America instead.

Early houses and farms in Toxteth Park

As well as erecting new homes, farms and mills, some of the Puritans occupied pre-existing buildings. Two of the earlier structures were once ancient hunting lodges, and now became the homes of the settlers foremost members, the Aspinwall family. These were the Lower Lodge (Otterspool) and the surviving Higher Lodge (that gave its name to Lodge Lane). Several other existing residences were taken over but the locations of these are obscure. It’s likely that Greenbank had existed as a farm house at this period (but that’s another post in itself).

Another Toxteth dwelling that almost certainly pre-dated the Puritans was Penketh Hall. This was at the edge of the forest of Toxteth and its border with Wavertree (Penketh means ‘head of the trees’ – edge of the forest). Penketh Hall is mentioned in the court rolls of West Derby in 1615 when Richard Haughton surrendered the house to the previously mentioned Puritan Edward Aspinwall. (Halmote Court of West Derby held on 18th December 1615). You can read more about Penketh Hall on another of my posts here.

Image: Liverpool Record Office

Liverpool merchants also took land in Toxteth Park

Puritans were not the only people that took leases, some Liverpool merchants also took advantage of this opportunity. This record below is from the town records of 1591, it shows that 100 acres was reserved for the inhabitants of Liverpool (that’s about the size of 57 football pitches):

The Mayor did make known unto the whole assembly that Toxteth park is to be disparked, and that my lord the Earl of Derbie’s [Stanley] pleasure is, that one hundred acres thereof or thereabouts shall be reserved to the inhabitants of Liverpool, such as will endeavour themselves to take the same, or such portion as they can conveniently deal with

Liverpool Town Records, 1591. Hand Book for the stranger in Liverpool, James Stonehouse, 1844

The Liverpool merchants included Robert More, John Bird and Giles Brooke. (see Hollinshead, 2007). Brooke was Mayor of Liverpool in 1591. He and John Bird had several mills in Liverpool and the surrounding area, even one at Birkenhead. Brooke had a brother called Humphrey who entered the history books as one of the men who gave warning that the Spanish Armada was gathering in 1586.

Plots for lease

Toxteth Park was divided into plots, these were subdivided by the names given to the fields, recorded mostly as ‘heys’. The majority of these plots were agricultural; Sea Hey, Horse Hey, Gorse Hey etc. But some offer intriguing hints to their past. Some also tell us that it wasn’t only men that had originally leased them; Judith’s Hey and Old Woman’s Hey (in two parts) can both be found on 18th century plans of the estate. These plot names survived well into the 19th century.

A Tithe survey was taken between 1845 and 1847, this listed the fields exactly the same as they were on an estate plan that was made in 1754, and probably had been since it had been disparked, or even earlier.

We can see from the 1765 map that the Dingle was made up of 3 plots, numbers 38, 39 and 40. Plot 38 was not inhabited in the 1760s but would later be known as Dingle Bank. Plot 40 had one house on it from 1688. Plot 39 had at least one house on at the turn of the 17th century.

Note: I have redrawn the plan of the entire Toxteth Park estate so it is easier to read – see Rimmer’s Farm section

The Holy Land in the Dingle

There are four Victorian streets in the Dingle that are known locally as the ‘Holy Land’. This is because they are named after figures from the Bible’s Old Testament. From the north these are Moses, Isaac, Jacob and David. But the first Holy Land in Toxteth Park was so-named by the Puritans, and the heart of it was the dell at the Dingle.

Before their chapel was erected in 1618, it was said that the Puritans gathered in the dell itself to worship. The oral tradition of this remained until 1812 when it first recorded by Dr. Thomas Raffles. Raffles researched the chapel but his findings were only published after his death via his manuscript, 1812 was the year he first came to Liverpool:

But though the population was scanty, it seems to have been of the right sort, for it consisted almost entirely of Nonconformists, and on that account tradition says that it was commonly called the ‘Holy Land! There was not a Churchman or a Roman Catholic in the whole district. The land being chiefly in the hands of the Dissenters, owing to the persecuting spirit of the times, they wisely resolved not to become the instruments of their own torment by admitting their enemies to take root in the soil.

They were in the habit of meeting for worship in a retired glen, then perhaps but little known, but familiar to us under the name of the’ Dingle;’ when one or two were placed upon the watch to give timely notice of the approach of informers. ‘Down with the Rump!’ was the cry that assailed them wherever they went, often mingled with the foulest abuse and the most horrid blasphemies. A relic of these prayer-meetings, for such they were, remained in the memory of persons yet living, when I went to reside in the Park in April, 1812.

Dr Raffles via The Christian reformer; or, Unitarian magazine and review [ed. by R. Aspland]. 1862

The Puritan’s made their mark on the landscape by giving Old Testament names to some of the places in their new home. A farm at Otterspool became ‘Jericho’ and the stream that ran past it became the ‘River Jordan’. The rocky outcrop on shore at the Dingle became ‘David’s Throne’ (see plan above). They named a cave below ‘Adam’s Buttery’.

David’s Throne

The Puritans must have held this outcrop in high esteem. It was named of course after the Biblical King David. In the Bible, ‘David’s Throne’ did not just relate to the physical seat of the king, instead it represented the establishment of the Jewish Kingdom. For Christians, Christ would also take on this ‘throne’.

As the angel Gabriel promised Mary: “He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the Highest: and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of his father David: And He shall reign over the house of Jacob for ever; and of His kingdom there shall be no end”

New Testament, Luke 1:32

It’s likely then, that David’s Throne at the Dingle represented the establishment of the Puritan faith in the ‘Holy Land’ they had been given. The Puritans would have believed it was God himself who gave them Toxteth Park through one of their own flock, Edward Aspinwall (Molyneux was just the middle man).

David’s Throne was the triangular outcrop below. The must have given a spectacular view.

Here is one of the amazing photographs that I’ll be sharing in the next installment. This features a rustic seat, placed by the Cropper family right on the edge of their ‘Dingle Bank’. This was close to Dingle Point and gives us a perfect idea of what the stunning view from David’s Throne was like.

The somewhat less awe-inspiring Camellia Court was built right on top of David’s Throne.

Adam’s Buttery

‘Buttery’ sounds like a strange name for a cave gouged out the rock face by the sea. But a buttery had nothing to do with butter, instead it was a large cellar, somewhere to store butts (barrels). Caves are still used today to store food and drink so it possible the cave at the Dingle served the same purpose. There’s a cave named Lady’s Buttery in County Mayo.

River Jordan

This stream still runs and was formed by joining of two brooks. The point where they met later became Sefton Park lake. The Jordan then runs (now underground) to Otterspool. To the Puritans, the Jordan would have been a perfect name for the watercourse that ran through their own ‘promised land’.

The Jordan River runs along the border between Jordan, the Palestinian West Bank, Israel and southwestern Syria. The river holds major significance in Judaism and Christianity. According to the Bible, the Israelites crossed it into the Promised Land and Jesus of Nazareth was baptized by John the Baptist in it.

Jordan River

Jericho

Why did the Puritans name one of their farms Jericho? Perhaps it was walled? More likely is that it was located next to the River Jordan.

For the tribes of the Reubenites and Gadites, along with the half-tribe of Manasseh, have already received their inheritance. These two and a half tribes have received their inheritance across the Jordan from Jericho, toward the sunrise.

The Boundaries of Canaan

(Genesis 15:8–21)

A farm house stood at Jericho until 1960, most likely erected by some of the earliest Puritan settlers:

Puritan education and worship – the Ancient Chapel of Toxteth

Discovering information of the homes of the Puritans is difficult, but not impossible. I have already covered Lower Lodge in great detail. This was the house of Mary Aspinwall and James Horrocks. The famous astronomer Jeremiah Horrocks was born there in 1618. You can read about Horrocks and his birthplace on my post here.

by E. W. Cox 1962.

Image and text reproduced with the kind permission of The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. Any reproduction must have the approval of the society.

If archives relating to their homes is scarce, we have a wealth of information on the Puritan’s school and chapel. By 1611, the Puritans had erected their school at the head of the Dingle stream. They appointed a 15 year old Richard Mather as its first master. By 1618 they had added a chapel and Mather became its first preacher. This amazing building still stands, although altered over the 5 centuries it has stood there. This drawing below shows how the school originally joined the chapel. Note also the narrow space between the windows and the corners of the building.

The building as it looks today is shown below. The chapel was enlarged in 1774 (note wider space between the windows and the corners). The school house at the back was changed in 1841.

Richard Mather

Mather had to leave Toxteth Park after being tried before a court to answer to his dissenting practices (including not wearing a surplus). He left for the ‘New World’ of America in 1645, just 15 years after the Mayflower.

As a thorough Puritan, Richard Mather had rejected all pomp and ceremony retained by the Church of England from its Catholic origins, and he preached at Toxteth without a surplice for 15 years before authorities discovered it. Suspended, and then reinstated, he returned to his dissenting practices and was tried before a court, before which he admitted without apology the matter of the surplice.

Permanently “silenced from Publick Preaching the Word,” he retired to private life and resolved to leave for America, where he would be free to preach and do good according to his own convictions. He and his wife (Katherine Holt, whom he had married in 1624) and their four sons sailed for America in June 1635 and arrived at Boston in August. His journal of the voyage is one of his best written works. His reputation had preceded him to New England, where several towns asked for his services. He chose Dorchester, Mass., a post he held until his death.

Richard Mather, Puritan clergyman, Encyclopaedia Britannica

A son of Richard was Increase Mather (1639-1723), he was also a Puritan minister in New England. Increase was also President of Harvard College (established 1636) from 1681 until 1701. Increase and his son Cotton played a significant role in the Salem Witch Trials (1692 – 1693). For more information see The Mather’s and the Salem Witch Trials in the Miscellaneous notes section.

The first (known) houses at the Dingle

Being near to a stream, forest and shore, it’s possible that dwellings and farm buildings may have existed in this area for hundreds of years prior to the Puritans arriving. Sadly, apart from the nearby Higher Lodge and Lower Lodge at Otterspool, the names and locations of these have been lost to history.

But this changes once we reach the 1600s. Just to the east of the chapel was another 17th century property called Elm House. This was erected on the plot named Chapel Hey so it’s likely that it built in connection with it.

Village Liverpool by Kay Parrott · Bluecoat Press.

The earliest know farm at the Dingle

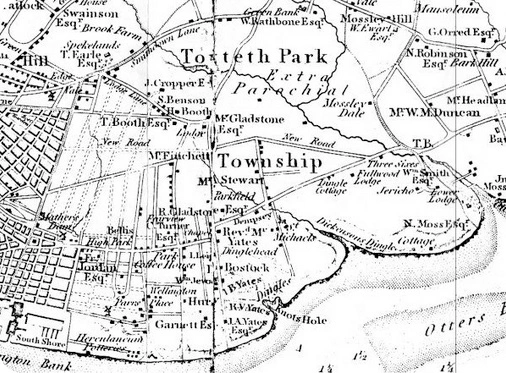

Near to the chapel, and closer to the Mersey, was a cluster of farm buildings. These were listed as ‘Rimmer’s’ when Yates and Perry drew their ‘Map of the Environs of Leverpool’ in 1768.

Note: One interesting feature of this map, is that at this point in history Park Road and Aigburth Road were one just continuous lane – Park Lane. This ran all the way to Aigburth Vale. If you wanted to travel further, you had to do so on the private road that led to Aigburth Hall. To do this you had to pay at the Aigburth Toll Gate.

Rimmer’s Farm was erected on one of at least two plots leased by the Puritans to be the new hub of their community. The path leading from the chapel to to the farm would become Dingle Lane by the mid 18th century.

Another 17th century building stood until the 1950s. This stood on the other side of Dingle Lane and was erected in 1688. Because of its proximity to Rimmer’s farm, it later was given that name. But I believe it may have been on a completely separate holding. It was not on School Hey, but instead on the Dingle plot in a field named Barn Hey after it.

(for both the farm and the building see Rimmer’s Farm below)

Toxteth Park Estate Plans

The earliest known (detailed) map of Toxteth Park is the aforementioned estate plan of 1754. This is now in such poor condition that it’s barely legible. What is important about this plan is that it shows some buildings, although very crudely drawn. Another estate plan was made in 1765. Although this shows the plot names, it does not show the occupiers. By 1765 there were approximately 85 buildings, although some (perhaps the majority) would have been farm structures and not dwellings.

Yates and Perry’s map of 1768 was the first to show some of the names of the residents, and one is included within the plot containing the Dingle. Two buildings are shown that were owned by a Liverpool physician named Dr Kennion (died 1791 – shown as Kenion). This was a descendant of John Kenion who was minister at the chapel from 1699 until his death in 1728. (I’ll come to the use of the double n later)

The Dingle stream dries up

At some point in history, this once strong watercourse ceased to run. Exactly when and how the Dingle stream ceased to exist was not recorded. It had certainly dried up by the very end of the 18th century. In 1790, Roscoe poetically put it down to the carelessness of a supernatural Naiad when he lamented its loss in a beautiful poem. Another, more plausible explanation given by Roscoe was that it had been ‘enfeebled by the scorching ray’.

I think I can provide a date. This rare plan of Toxteth Park (Robert Lang, 1754), and another from 1765, both show the stream, albeit much reduced in flow. The gorge cut out of the Dingle shows that at one point in history this must have considerably stronger.

Lancashire Archives.

The estate plan from 1765 (repeated above) has the stream coloured blue (indicating it still ran at that point). By 1790 when William Roscoe was living nearby (possibly at Elm House) the stream had dried up. Therefore, the date the stream stopped running was most likely between 1770 and 1780.

I believe the real cause for the stream drying up wasn’t natural (or supernatural), most likely it was the hand of man that caused its demise. Since the 1660s the Lords Molyneux had dammed the source of the streams – the Moss Lake. One of these, ‘Mather’s Dam’, can be seen on old maps. Another dam was located close to the town boundary at what would become Parliament Street. This street was named after the Act of the Parliament that Molyneux had been awarded in 1775 to allow him to lease his land for development. Originally a large stone wall ran it’s entire length, this was known as ‘the Great Wall of Toxteth Park.’ (Liverpool in the Reign of Queen Anne, page 114)

Dr Bostock

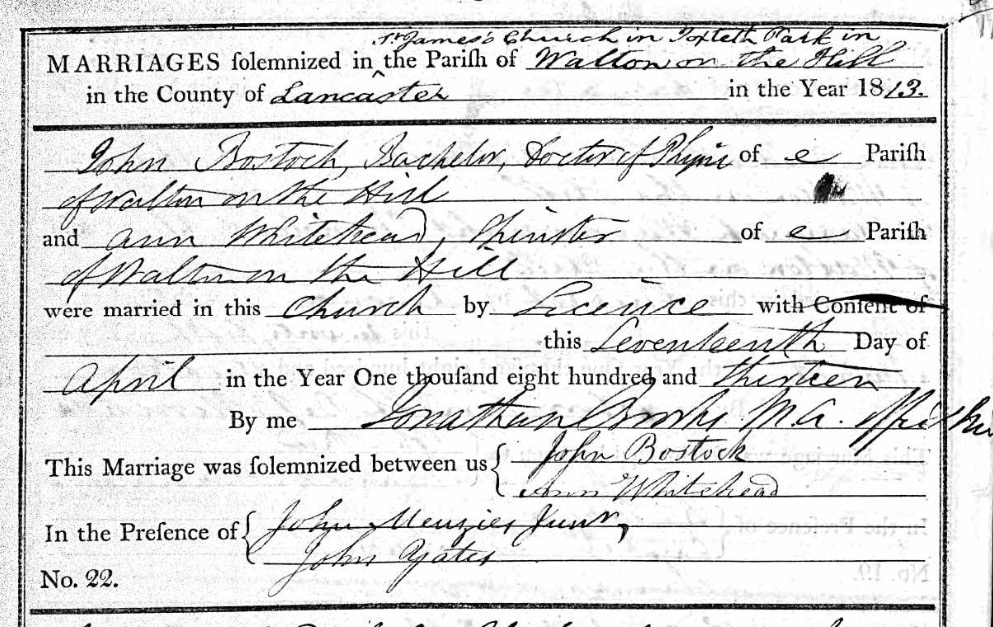

No other names appear on the 1768 map, instead Knot’s Hole is listed as a geographical feature. The fields to the north of it (later known as Dingle Bank) are all named after Knott’s Hole. But from the late 18th century another name appears in connection to the area, Dr (John) Bostock. His son, also John would also live at the Dingle.

Yates’ Dingle

The younger Bostock married Elizabeth, the daughter of John Ashton of Woolton Hall. It’s likely that the daughter of such a prominent merchant and landowner had given the Dingle to his daughter as a marriage gift. After Bostock’s death, Elizabeth married again, this time to the Rev. John Yates. Yates had a great interest in education, he’d had his eyes set on the school prior to the marriage. Now, via a very convenient marriage, Yates became the possessor of a large area of land adjacent to it. From that moment on, the name Yates family would be forever associated with the Dingle.

I’ll cover the Yates family together with the other famous residents of the Dingle, the Croppers, in the next installment.

17th century

Rimmer’s Farm

‘Rimmer’s’ Farm’ appears as such on the 1768 map but a farm had been there since at least the 17th century (possibly since the chapel was erected or even before). The name of the farm in the 17th century is not known, but the Rimmer family had it from at least mid 18th century. As yet I have been unable to track down who the Rimmer family of Toxteth Park were. But it that may be because they never lived there. Instead they might have just leased the farm off Molyneux.

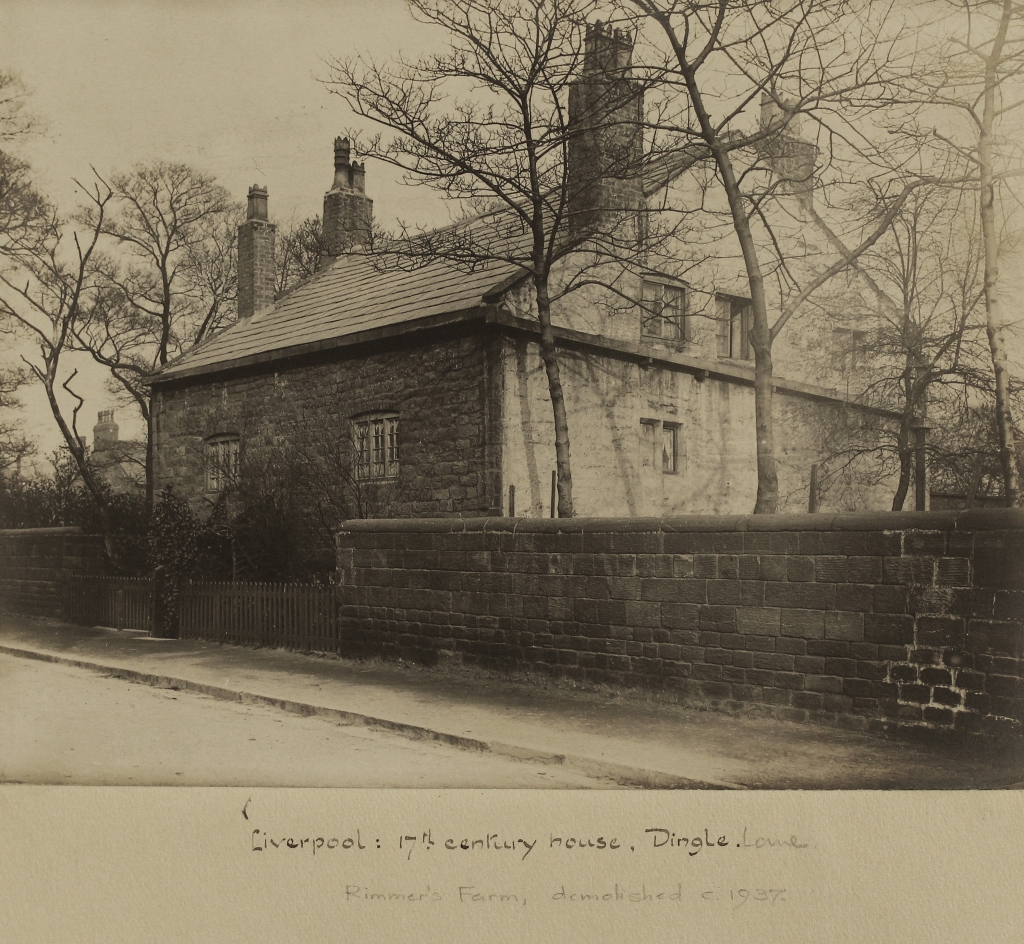

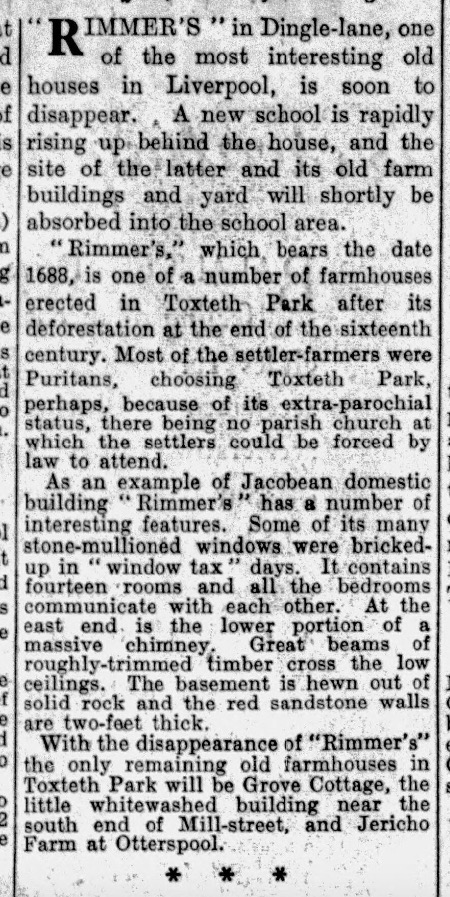

A house erected in 1688

This house below stood on Dingle Lane and had a date stone of 1688. In his 1907 history of Toxteth Park, Robert Griffith suggested this had been part of Rimmer’s Farm shown on the 1768 map. Philip Mayer also stated this in his 1996 book A Tram Ride to Dingle.

Rimmers Farm, Dingle Lane 1920s

A Tram Ride To Dingle, Philip Mayer, Bluecoat Press, 1996

Rimmers Farm was known by this name for over 100 years. The fields around being recorded as “farm fields”. When the Misses Yates had their mansion built (sometime

between 1825 and 1835), they called it “Farm Field”,

although, by the start of the twentieth century, it had been renamed “East Dingle”. The last part of Rimmers Farm, shown here, bore the date 1688 on the outside and was on the side of Dingle Lane exactly opposite Dingle Mount. The old building was demolished some time after 1938, at which date it stood next to the newly built Shorefields School.

See also Was the 1688 house really part of Rimmer’s Farm? in Miscellaneous notes.

Rather than Rimmer’s, the house was known as Yew Tree House (also Yew Tree Cottage) in the 1820s. Two gardeners are listed in Baines directory of 1824 lived there, James Holcroft and Robert Thomas. Elsewhere in the directory a joiner named William Morrison was also shown as living there. The house looks small for three men to share it, but as we’ll see later on it had a considerable amount of rooms and bedrooms.

Then, from before 1871 it was named Ivy Cottage. The early census records did not record the names of the houses, but the 1781 census shows that William Atkinson lived there. He was a gardener from Cumberland. Another gardener shared the house, he had the appropriate name of James Rose.

In 1911 it was occupied by a clerk in the timber trade named William Henry Kewn, and a dock labourer for Mersey Docks and Harbour Board named Henry Highlet.

This photograph below is by James A. Waite. It appears in an amazing photographic album of historic houses in Lancashire and Cheshire held by the Liverpool Record Office. Waite took these photographs between 1888 and 1921. You can see that the Rimmer’s farm attribution had been added in pencil after it was demolished in 1937.

A drawing of Ivy Cottage

A wonderful pencil drawing of this house was made in 1873 by John Barter. This can be found in the archives of the Liverpool Record Office. This was a preliminary sketch for a painting that does not seem to have been made, or is now lost. It shows a rural Dingle Lane with a road sweeper, and a farmer leading his cows and sheep from the fields below. A couple can be seen taking a stroll, the woman is holding a parasol. Three chimneys are shown on the house, another was located at the back (see photo above). The house had a rustic entrance and fence. Beyond the house is dense woodland. At the end of the view is a small structure, this was almost certainly the lodge belonging to the neighbouring house named West Dingle. The front of the appears to be covered in ivy. Right next to it is a large tree, probably a yew. No doubt these led to it being called both Yew Tree Cottage and Ivy Cottage.

Note: The drawing is very faded and the lines extremely faint, so I have traced over the lines in Photoshop to make the image clearer :

The original owner of this house is not known, but I can speculate based on the date and the location. Michael Briscoe had been the minister of the chapel up to his death in 1685. Then it was Christopher Richardson who was co-pastor with Thomas Crompton. Richardson was responsible for the first congregation of Presbyterians in Liverpool, he preached alternately at Toxteth Park and in the town of Liverpool. This was from 1687 or 1688 – after a liberty passed by James II – the same time that the house was erected. Richardson died in 1698.

Whether or not it was Richardson who erected the house, it gives us an opportunity to see the faces of people who lived in the area at that time. This is Rev. Christopher Richardson and and his 2nd wife wife Hephzibah Richardson, née Pryme. You can read a love letter between these two here.

The produce of Rimmer’s farm

Rimmer’s Farm was on plot of land was on the same plot as ‘School Hey’. It’s almost certian therefore that the farm was leased by the chapel’s congregation. The farm itself was likely to be older than 1688 and more likely was the same age as the school (1611).

Rimmer’s wasn’t just any old farm, it likely supplied the school and chapel with everything they needed. By reading the names of the fields we can discover it had crops, sheep, cows, pottery, marl (minerals excavated to improve the soil) and slate. Fish would have been caught on the stretch of shore it owned. Fresh water was taken from the rectangular pond next to Elm House next door. Also behind the chapel was a smithy. All this would have made the school and chapel self-sufficient.

Regarding fishing, another interesting feature can be see if we zoom into the Dingle Point area of Lang’s map (left of the compass). What appear at first glance to be a series of ink blots, were actually fisheries comprising a line of conical fish traps. These are much clearer on his section covering the shore between Dickenson’s Dingle (later St. Michael’s Hamlet) and Jericho. The site at Jericho reminds us that there was once a fisherman’s cottage on the shore that survived well until 1933.

The 1688 house was demolished to make way for Dingle Vale School (later named Shorefields now called King’s Leadership Academy). The site of the building is under the car park. I have coloured the site red. ‘East Dingle’ is next to it (this was actually ‘Farmfield’ as far as I can tell, this house was only called East Dingle on late 19th century maps). On the tithe schedule of 1845, both the mansion and the 1688 house are number 451. These were owned and occupied by the ‘Misses Yates,’ being Anna Maria and Jane Ellen Yates. The other land on the same plot, 452, was farmed by Richard Wareing (This was Dingle Farm leased by Thomas Seddon in 1825).

Building tenders had been advertised on the 1st February 1937. An article from October of the same year describes the 1688 building just before it was lost.

But the house wasn’t demolished immediately, it was still standing when some of the first pupils attended the school. In 1973 the Echo printed a letter from Mrs Edna Sutton who attended the school. She remembered that the house was still on the grounds and left open, so she went in to have a look around. She recalled that the ceilings were so low that she couldn’t stand upright in places, and she was only about 5′ 6″. She must have been referring to the doorways because Griffiths stated that the rooms ‘were little over seven feet high’

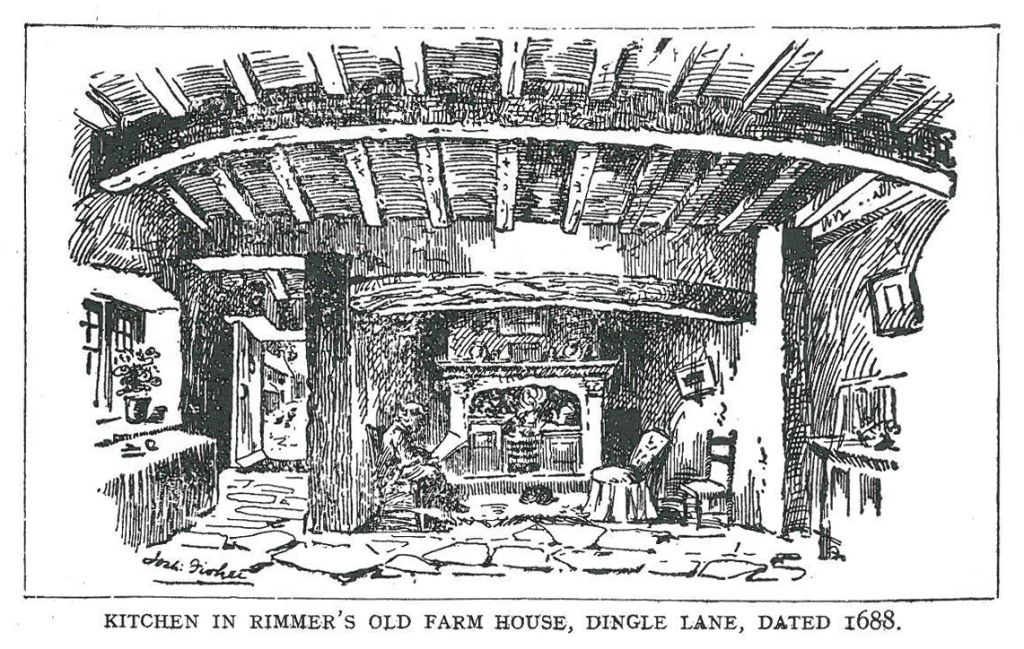

The interior

The Daily Post article had taken the description of the house straight from Griffiths. We are extremely fortunate that he described it in great in 1907. He even commissioned Joshua Fisher to illustrate the kitchen. If you look closely at the open door you can just make out the Farmfield house.

“Rimmer’s Farm” was known by this title for over a hundred years, and appears to have been of considerable importance, the fields for some distance around being known as “Farm Fields.” In the early~part of last century, when the Misses Yates, the late public-spirited proprietresses of Dingle Glen, erected their mansion on the beautiful grounds overlooking the little bay known as “Knott’s Hole,” they took for the name of their house the sobriquet of the ground on which it stood, and called it “Farm Field.” The mansion is now known as “East Dingle.”

Of the different buildings which constituted “Rimmer’s,” only one now remains, an ancient-looking farm building bearing the date “1688 ” on the outside, and situated on the side of the road exactly opposite Dingle Mount. It is the interior which at once reveals to the visitor the age of the structure. The building, while so insignificant from the outside, is of great breadth, and contains fourteen apartments; and although only two stories high has nine bedrooms, all communicating with each other. The basement is hewn out of solid rock, and the walls are over two feet thick. The little mullioned windows are fitted with lead-lights and sunk in deep recesses of the solid walls, many of them have been bricked or plastered up to avoid the window tax in the early part of the last century.

The ceilings are low, exhibiting the rafters, in some cases the untrimmed wood of the tree. None of the apartments are much over seven feet high. Across the timbered ceiling of the ancient kitchen runs a massive beam, behind which was once the old open fireplace and ingle nook. The present fireplace and chimney breast is a modern addition, but beside it there is still the cavity in the stone floor where the wheel which connected the great spit with the smoke-jack in the chimney, once revolved, reminding us forcibly of the good old times, with plenty of wood fuel, the blazing faggot lying in the great iron-dogs, the homecured hams and bacon hanging in the farmer’s chimney, and the great spits merrily turning-in preparation for the Harvest Home or English merrymaking,

The History of the Royal & Ancient Park of Toxteth, Robert Griffiths, 1907

“When all the neighbough’s chimneys smoke,

And all their spits are turning,”

The house can be seen on this close up of another aerial photograph from the 1920s.

I believe that the 1688 house may have later been the home of Dr Bostock (see further down this post)

18th Century

John Kennion

Not long after the Dingle Lane house was erected in 1688, we have evidence for the first occupier of the Dingle itself. This was John Kenion (also Kennion, born 1673 and minister at the chapel from 1699 until his death in 1728). His descendant, the Liverpool physician named Dr Kennion (died 1791) appears on the 1768 map. His house(s) appears opposite the chapel in top left hand corner of the Dingle estate.

A report made in 1718 mentions Kennion’s name with ‘Park Chapell’. It wasn’t ‘ancient’ yet – but still 100 years old:

Park Chappell.

A Building within Toxteth Park called the Park Chappell in possession of and used by Mr. John Kennion as a place for divine service.Schoole.

The Ancient Chapel of Toxteth Park, Lawrence Hall, 1935, HSLC

A Building thereto adjoining in Toxteth Park aforesaid in possession of and used by William Huddershall as a School house which they hold as tennants att Will without any Rent.

Kennion’s House is very prominent on the 1786 map below, it overlooked the chapel with just what would later become Dingle Lane between them (I’ve coloured both red). Kennion’s house was known as ‘Dingle Head’ – because it was built at the headwater of the Dingle stream.

Because of the continued ownership by the Kenion/Kennion family, we can can be confident that the Dingle plot was not owned by the chapel. Otherwise, rather than staying in the Kennion family, it would have been taken over by the ministers who succeeded him. After Kennion, the minister was Thomas Gellibrand (until 1737), and William Harding until 1776. (see this paper of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire)

Members of the Kennion family were buried in Ancient Chapel. Alice Kennion (died 27th January 1813) has a memorial tablet on the wall. She was the wife of John Kennion whose memorial in next to hers.

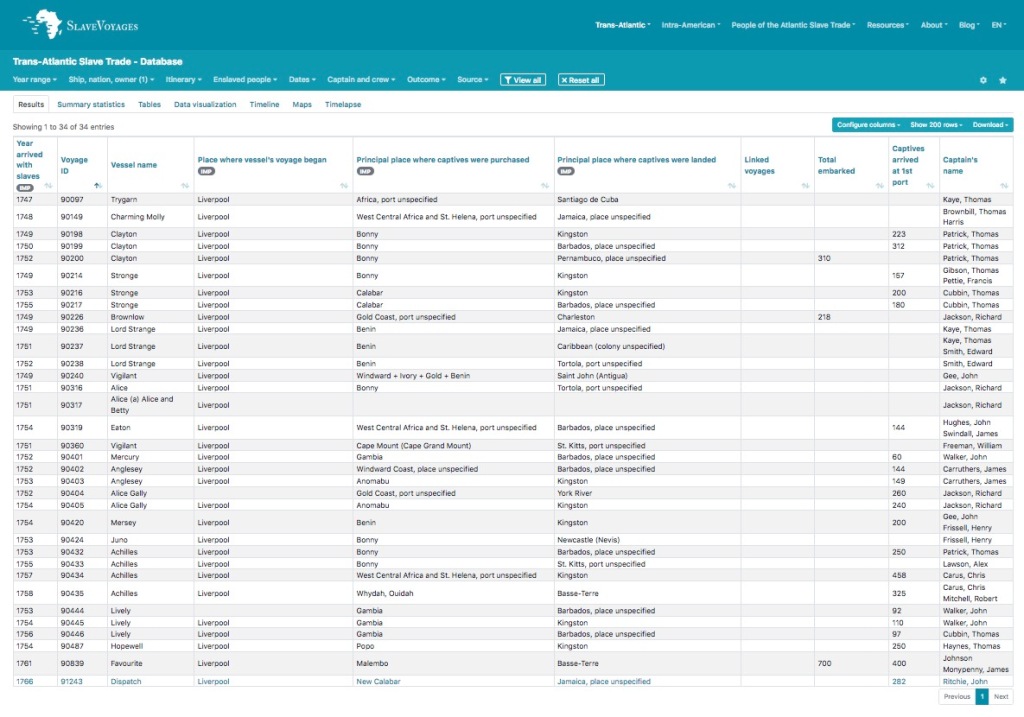

Before we get too carried away with the idea of the pious Kennion family living in a rural idyll, let’s pinch ourselves and remember we have now reached 18th century Liverpool. The indelible stain of the African slave trade was bound to appear at some point…

Kennion family and the slave trade

In the 1760s John Kennion appeared as a physician with his surgery at Drury Lane, Liverpool in Gore’s street directories. His name is spelt Kenion as the map. In 1774 and 1774 he was at 17 Water Street. At the same time there was a merchant named John Kennion (double n) at 1 Peter Street, College Lane. By 1778 there was a whole raft of Kennions with various spellings. Dr Kenion was still at Water Street, but there was a surgeon named John Kenyon at 34 Ormond Street. These all appear to have been of the same family, the variations in spelling may have been to differentiate between them.

The Kennion family were also heavily involved in the slave trade. John Kennion and his wife Alice who have memorial in the Ancient Chapel were just one branch of the family who owned enslaved people. John was the Collector of Customs in Liverpool, but he was also a ‘Major slave-owner in Jamaica’. These were the Mona slave plantation, the Hall Head slave plantation with John Hall (his cousin from Liverpool), and finally the Holland Estate. He sold the Holland Estate in 1771 for the staggering sum of £109,000 (a value of over £15 million today):

The first issue of the Colonial Journal in 1816 opened with an image of Hall Head, the property of John Hall of Liverpool. The commentary following said: ‘In the year 1760 the Hall Head estate together with the Holland and Mona estates, were in the possession of the late John Kennion, also of the vicinity of Liverpool.’ According to this source, Kennion had sold Holland to Simon Taylor for ‘one hundred and nine thousand pounds’; Mona was [in 1816] the property of [unknown] Milner, Esq.; and Kennion had bequeathed Hall Head to his cousins John and [unknown] Hall, the former of which had since purchased his brother’s share.

John Kennion of Liverpool, The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery

When John died, Alice inherited his slave plantations, see here.

How can we be sure that they were the Kennions who lived in the house in the Dingle?

As there were several John Kennions (also appears as Kenion and Kenyon), it is important to identify which person had interests in the slave trade. The memorial above is in the Ancient Chapel of Toxteth. It is for Alice Kennion, the memorial for her husband John is next to it.

This other memorial below (also in the chapel) resolves at least two of the Johns. The John Kennion (double n) that owned slave plantations with his wife Alice, was the son of John Kenion (single n) who was the minister from 1699. Records with the Kenion spelling almost always relate to the minister (italics are mine):-

The REVD – MR. JOHN KENION,

died Aug. 16th – 1728, Aged 55. (so born circa 1673)

MILICENT KENION, his wife,

died Decbr. I5th I732, Aged 58. (so born circa 1674)

JOHN KENNION, ESQR. Collector of Customs, Liverpool,

died the 20th of June, 1785, Aged 59 years. (so born circa 1726)

ALICE KENNION, his wife,

died the 27th of Jany. 1813, Aged 83 years. (so born circa 1730)

This book mentions that mentions that the younger John had a brother who was ‘an eminent physician in Liverpool’. The only doctor or surgeon named Kennion (and variants) I can find in the directories was called John, so this person could not have been his brother. Instead, the author didn’t realize that the doctor and the collector of customs was the same person. Kennion was only collector of customs between 1782 and 1785. Further proof is that in 1783 (the only directory that covers his tenure as collector) only the doctor is listed.

The Online Archive of California has records relating to John and Alice Kennion’s involvement in the ‘Hall Head’ plantation amongst their Hall Family Papers and Sugar Plantation Records. Two documents relate to his house in Toxteth Park. The first is a copy of the Toxteth Park taxes he paid in 1785. The other is a deed relating to the sale of the house that says it was ‘most pleasantly situate near the chapel in Toxteth Park’:

To be sold by Auction

At the house of James Gore, the King’s Arms Tavern opposite St James Church this present Monday the 21st day of January 1783 – at 4 o’clock in the afternoon –A good modern built dwelling house, fit for the summer retreat of a genteel family with about 26 large Acres of rich land contiguous, most pleasantly situate near the chapel in Toxteth Park. The house has 4 rooms on a floor with commodious dry cellar. And there belong to it a good Garden, a large orchard well stocked with fruit trees, a spacious Barn, a stable for five horses, a shippon for 12 cows, and a well of very fine spring water ; the outbuildings are built of good stone and all the buildings are thoroughly slated.

The premises now produce a clear rent of £78 for the remainder of term which will expire next Candlemas….

Sale of land at Toxteth Park near Liverpool, England for which John Kennion, Hugh Kirkpatrick Hall’s agent in London, paid the taxes in 1785 (1783 February 24 and 1785). Hall Family Papers and Sugar Plantation Records. Online Archive of California

That document proves that John Kennion and his wife Alice lived at the house later known as Dingle Head. There can be no doubt of that house’s link to the slave trade.

As an aside, the sale mentions the building was a ‘good modern built dwelling house’. This indicates that the house had been rebuilt or improved recently. The house his father had lived in from the late 1690s would be at least 80 years old by then. It also states that the estate was ’26 good acres’. If we use this tool to calculate area, we see that 26 acres is not a bad match for plot 39 on the 1765 estate plan.

The database for owners of slave plantations mention several John Kennions. One known as ‘John Kennion, late of Jamaica‘. Another Liverpool-based John Kennion was the joint owner of slave ships. A list of these is shown below from the Slave Ship Database (search owners for kennion, john). The other partners in these slaving ventures varied but Peter Holme joined him for 20, under the trading name of Kennion & Holme.

John Kennion’s connection to John Newton, author of Amazing Grace

The most famous, and infamous, of Kennion’s slave ships was the Brownlow in 1748. This was the first ship that John Newton took to Africa. Newton would later captain his own ships, on this voyage (fresh from being a land-based slaver in Africa) Newton was first mate.

Newton’s captain was a sadistic lunatic named Richard Jackson. There was an uprising on the Brownlow by the newly-enslaved Africans. Captain Jackson (no doubt assisted by his First Mate Newton) responded with barbaric cruelty – by cutting the limbs off the ringleaders, piece by piece, this Jackson called ‘Jointing.’ John Newton recalled this incidence in a private letter in 1788 (40 years after it happened):

Some of them he jointed; that is, he cut off, with an axe, first their feet, then their legs below the knee, then their thighs; in like manner their hands, then their arms below the elbow, and then at their shoulders, till their bodies remained only like the trunk of a tree when all the branches are lopped away; and, lastly, their heads. And, as he proceeded in his operation, he threw the reeking members and heads in the midst of the bulk of the trembling slaves, who were chained upon the main-deck.

Letter from John Newton to Richard Phillips, 5th July 1788. Memoir of the Life of Richard Phillips

by Mary Phillips. See also Markus Rediker, Slave ship; A human history

218 people were taken in chains from Africa and forced onto the Brownlow, only 156 survived (28.0%). The Brownlow would not be the only ship that Jackson captained that had a higher than average mortality rate. 95 out of 190 enslaved people died on the New Eagle in 1759-1760 when – exactly 50%.

For more information about John Newton and his time in Liverpool, visit my other website Bygone Liverpool, this was a collaboration with Darren White:

John Newton in Liverpool – From slaver to customs official

This second post was a colloboration with the Cowper & Newton Museum in Onley.

John Newton in Liverpool, Part 2. Locations and connections

John Bostock

As can be seen from the acreage owned by John Kennion, he only owned/leased the top of the three plots of the Dingle. The middle was owned by someone else. This was Dr John Bostock (1743–1774) through his wife Elizabeth (1749-1819). Elizabeth was the daughter of John Ashton of Woolton Hall). This beautiful portrait of Elizabeth was painted circa 1765 by Joseph Wright of Derby, ‘one of five he painted of members of her family, which were fitted into the paneling of the dining room of her brother’s estate, Woolton Hall’

Image and text: Denver Art Museum

Bostock was born in England but educated in Edinburgh and graduated in 1769.

Bostock became an extra licentiate of the College of Physicians of London in 1770, and began practice immediately after at Liverpool. He was elected physician to the Royal Infirmary, married, and had a son, Dr. John Bostock. and but died when only thirty-four years old, 10 March 1774. Some of Bostock’s books are preserved in the library of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society in London, and among them a copy of his ‘Tentamen Medicum inaugurale de Arthritide,’ Edinburgh. 1769.

John Bostock (1740-1774) Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900

He married Elizabeth at St Peter’s church (Church Street) on 17th September 1771. Two year later, on 29th June 1773, their son John was born. It is the younger Bostock who appears on the maps (James Sherriff 1816 and 1823). This is because the father died in 1774 when he was aged just 34.

Bostock was educated at Hackney under Joseph Priestley (scientist and discoverer of oxygen). Bostock then studied as an apothecary in Liverpool before studying medicine at Edinburgh. He graduated in 1798 (like his father 30 years previously). His accomplishments are too numerous to list in their entirety here.

In letters that Bostock wrote to medical journals, he gave his address as Knot’s Hole Bank, like this example is from 1812. Bostock can also be found in botanical journals, often noting examples of plants he found at Knot’s Hole, in this example he describes finding Small Upright St. John’s Wart.

If we return to Sherriff’s map of 1823, we can see where Bostock’s house was located. The inclusion of his name is confusing because he had left for London by 1817.

The discover the location of Bostock’s house we need to look at maps dating from after he left. On Sherriff’s map, Bostock’s was above that of Joseph Brooks Yates and very close to the house dated 1688. I have coloured the 1847 Tithe plan and added a key for the owners. Joseph Brooks Yates house was called West Dingle, the plot above was Farm Field (also recorded as Farmfield). The 1688 house was on the Farmfield plot, so it’s highly likely that this was the Bostock house.

The map also shows the Dingle dominated by houses owned by the Yates family. This is because Bostock’s mother had remarried after his father’s death. Her new husband was Rev. John Yates. Through this marriage he came into possession of the middle plot of the Dingle. Yates would then purchase the top plot that had been owned by John Kennion (See Yates’ Dingle in the next installment)

©Jim Kenny, The Priory and the Cast Iron Shore

In fact, even though Bostock gave his address a Knot’s Hole Bank, the only other house near to what would later be called Dingle Bank (coloured purple above) prior to the Cropper family moved there in 1823 was the home of John Aston Yates (James Sherriff’s maps of 1816 and 1823). This was probably erected circa 1815. Prior to 1823 the only other buildings on Dingle bank itself were single-storey farm buildings. But in Bostock’s day there was no dwelling. In 1925 Frances Anne Conybeare described Dingle Bank before the Cropper family erected houses on it:

they [Yates family] have built, just within the gate, a massive lodge of sandstone, and also at no great distance, an ample range of stabling, with a walled garden and greenhouses beyond; but there they stopped short, and never raised the mansion they had planned for themselves.

Dingle Bank; Home of the croppers. Frances Anne Conybeare

Given that information, it is highly likely that Bostock lived in the 1688 house, later known as Ivy Cottage.

We’ll return to Elizabeth Bostock in the next post as she later married Rev. John Yates.

Roscoe’s Botanic Garden

Bostock was a great friend of William Roscoe. Along with Dr Rutter, Bostock helped Roscoe set up his Botanic Garden in 1799.

Dr Bostock, the first person to describe Hayfever

Perhaps Bostock’s lasting legacy is that in 1819 he was the first person to describe Hayfever. The link between sugar and diabetes was also discovered by a Toxteth Park man. See Miscellaneous notes

Back to the slave trade…

Joseph Wright’s painting of Elizabeth Bostock was acquired at an auction in 1996. The seller was David Ashton-Bostock. The description includes this revealing paragraph:

Joseph Wright (“of Derby” denotes the English city where he passed most of his working life) spent two years in Liverpool painting portraits of middle-class families made wealthy from the city’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Elizabeth Bostock belonged to one such family.

Denver Art Museum

This refers to her father John who made ‘a large fortune as a merchant, salt manufacturer and slave-trader’. You can read about the Ashton family’s links to salt and slaves on this Bygone Liverpool post. But it appears that the Bostock family had also been heavily involved in the slave trade.

In 1752, a John Bostock appeared in a list members of the African Company of Merchants. There were several Bostocks in Liverpool so there is a possibiblity that it was a different family. But, Anne Holt’s 1938 book Walking Together: A Study in Liverpool Nonconformity, 1688–1938, mentions that religious identity was an important factor prior to 1740. In this paper from 2008, Brian W. Refford included a list of over 30 of these that includes John Bostock, John Kennion and Joseph Manesty.

In the 1756, a John Bostock appeared in an advertisement for a house at Low-Hill (now the Kensington area). Bostock was acting as an agent but the advertisement was paid for by Joseph Manesty. Manesty is (in)famous as being the employer of John Newton (the slave ship captain who became a religious minister and wrote the world’s most hymn Amazing Grace). The reason these two names appeared together is that John Bostock jointly owned at least two Privateer ships with Manesty. (see this Bygone Liverpool post).

But who was this slave trading John Bostock? It couldn’t have been the elder Bostock because he was only born in 1740. It’s possible that it was his father, also John Bostock (born circa 1702 and baptised at Childwall).

Note: Another Bostock appears on the Slave Ship database as owner of Liverpool ships from the 1770s. This was Robert, but he was the son of Peter of Tarvin, Cheshire.

John Ashton Bostock

The Bostock and Yates family continued their links. The 1851 census shows that John Ashton Bostock (1815 – 1895), son of John Bostock (1773 – 1846), was a visitor to Joseph Brooks Yates’ house West Dingle. John Ashton was born at the Dingle, but grew up in London when his father moved there in 1817. Like his father and grandfather, John Ashton also entered the medical profession, but this time in the army – he was surgeon to Queen Victoria.

Another continued link comes through the legal case of Yates, Bostock vs D’Enycourt. This dispute arose in 1891 over the Dingle estate owned by Rev. John Yates. Yates had died in 1826 so this dispute was 65 years after his will!

Industry and working class housing come to Toxteth Park

Up to the 1770s, Toxteth Park had remained rural, but Molyneux had plans for it. In 1768 Charles William Molyneux (1748 – 1795, son of Thomas Molyneux who commissioned the 1754 Toxteth map) was an MP that had been elected to the House of Commons. In 1771 he turned his back (publically at least) on Catholicism and conformed to the Church of England. He was given the title Earl of Sefton in return.

In the same year, Earl of Sefton had plans to develop Toxteth Park for housing and industry. In 1775 he obtained an Act of Parliament to grant building leases. He named the boundary with Liverpool ‘Parliament Street’ to commemorate this. He employed Cuthbert Bisbrown to lay out the area that was to be named Harrington.

Bisbrown was born in 1836 at Poulton Le Fylde. He moved to Liverpool between 1751 and 1762. When he married in that year he was listed as ‘timber merchant of Liverpool’. He appeared in a list of duty paid to apprenticeships in 1762 when his occupation was a cabinet maker. In Liverpool’s first street directory of 1766, Bisbrown was living in Paradise Street and had added ‘Builder’ to his trades. By 1774 he had moved to Brook Street and his occupation was then surveyor mapping. Bisbrown also built, and probably designed, St. James’ Church (1774–75).

Harrington was named after Isabella, Molyneux’s wife. She was the First Countess of Sefton and daughter of the second Earl of Harrington. The first land to be developed was the farm of Thomas Turner. Turner’s name appears in the margin of John Eyes’ plan of Liverpool (1765).

Just above the gate is where St. James’s church would be built in 1774–75 by Cuthbert Bisbrown, his name appears on plot No. 4 showing he had recently purchased Edmund Odgen’s land. Thanks to Darren White for the map.

By the time this plan of Liverpool and its environs was drawn in 1806, the grand plans of Harrington were still mostly restricted to the drawing board.

The Harrington project failed. Bisbrown faced financial difficulties because American War of Independence, and was bankrupt in 1777. He died in 1788 and was buried on 8th February at St James, the church he erected. His final occupation was Architect.

On the 1806 plan above you can see the streets laid out for Harrington, including Sefton Street. 30 years after the scheme had started, the majority of streets were still merely proposed. It’s interesting to see that the bottom 3 squares of the grid are actually over the (as yet unrecaimed) Mersey.

Bisbrown’s plan would prove disastrous for the people that would later live there. Picton, writing in 1875, blamed his grid on the insanitary court housing that would later occupy this area. Future developers would cram in as many houses and souls into each section:

In laying out the land a grave error was committed, the results of which have been very serious, and will operate injuriously for ages to come. The leading lines of street were laid out judiciously enough at right angles, and of ample width; but the interior of the blocks so divided was left to be arranged as chance or cupidity might direct. Hence arose subdivisions of mean, narrow streets, filled with close, gloomy courts, into which as many dwellings as possible were packed, irrespective of light and air. The result has been the impression of an inferior character on this quarter of the town, which it has never been able to recover.

Memorials of Liverpool : historical and topographical, including a history of the Dock Estate, James Allanson Picton, 1875

Industry in Toxteth Park had been restricted to watch-making, water and wind mills and a limited amount of ship building. Now a copper works polluted the air. Charles Roe had erected a copper works in Liverpool in 1767, but after complaints about pollution he relocated to Toxteth Park and poluted that instead. This later became a pottery works, it’s said that the first pottery mad there had a green tint because of the pollution that was still in the air from Roe’s factory.

Parts of the shore became docks, and fields became timber yards. A ‘forest of masts, and chimneys belching toxic smoke would overtake oaks and windmills to dominate the skyline of the north end of Toxteth Park. Houses would be needed for the influx of workers, and churches would be required to keep them in check. The Jerry-built houses of Harrington would soon be fit to burst. More houses were erected ever southwards. The dawn of what would later be considered the Dingle was on the horizon.

The southward sprawl of industry and housing would be kept back by one family, the Yates. They drew a natural line of defense at Dingle Lane, and then continued their fortification of trees eastwards with Prince’s Park. The ‘perfect paradise’ of the Dingle would remain for over a hundred years. Prince’s Park is still with us.

You can read an excellent post on Harrington by Dr Thomas McGrath here.

I’ll return to industry in Toxteth Park throughout this series. The next installment will cover the Yates family from the late 18th century, and the Cropper family of Dingle Bank.

Miscellaneous notes

Original location of the Dingle

The Wikipedia entry for the Dingle lists what is commonly considered to be the boundaries of the area:

Some locals regard Dingle as being within the area encompassed by Warwick Street, in the north, Princes Road, Devonshire Road and Dingle Lane. Some define the Dingle as above but only as far as Grafton Street and not to the bank of the Mersey, as this area was part of Liverpool Docks.

Dingle, Liverpool. Wikipedia

But well into the 20th century, the area known as the Dingle mostly related to the top of Aigburth Road – and this was completely outside the area above. This was because this was the location of the actual Dingle Vale. Within this area was also the first houses to be named after it; Dingle Head, West Dingle, East Dingle and Dingle Cottage.

The land that gave the area its name spanned this area in modern Liverpool:

North boundary: Dingle Lane

South boundary: The North side of Alwyn Street

East boundary: Aigburth Road

West Boundary: The shore (this used to reach as far as the modern Riverside Drive)

I have marked the area on these side-by-side maps below. The map on the left is circa 1892 when the terraced houses of Alwyn, Rosslyn, Errol, Sandhurst, Blythswood, Lambton and Colebrook were halfway completed.

A photograph (circa 1916) of an old bakery cart for Wallers bakery, 74 Aigburth Road (corner of Blythswood Street), says it was in Dingle. Much later Dave’s Dingle Diner would be situated on the same block.

Even as late as 1962, this map below shows Dingle south of Dingle Lane.

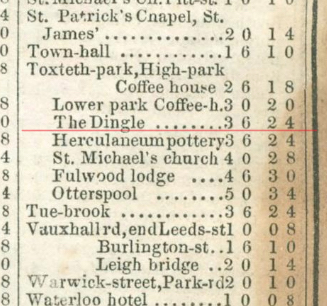

I believe that the later perception of the Dingle area came about because the chapel on Park Road was the stop for hackney cabs and trams from central Liverpool. In 1896, Dingle train station would be erected almost opposite. This was an underground station but actually part of the Overhead Railway system. A traveller purchasing a ticket to visit the Dingle would exit on Park Road, and not Aigburth Road. Anyone who lived or had a business near to the station would naturally say they were from the Dingle as the station had become a famous marker.

Bradshaw Companion, 1834

Likewise, the area south of Dingle Lane became commonly known as Aigburth, even though that doesn’t begin until after Aigburth Vale.

To add to the confusion, there was also another Dingle very close by, this was Dickenson’s Dingle and it became St Michael’s Hamlet thanks to an enterprising iron merchant named John Cragg.

Mather’s sons and the Salem Witch Trials

A son of Richard was Increase Mather (1639-1723) was also a Puritan in New England. Increase was President of Harvard College (established 1636) from 1681 until 1701.

A reminder of what period of history we are discussing, is that Richard Mather’s son and his grandson Cotton, played an important role in the Salem Witch Trials of the 1690s.

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, 19 of whom were executed by hanging (14 women and five men). One other man, Giles Corey, was pressed to death after refusing to enter a plea, and at least five people died in jail.

Salem witch trials

Like many people in the period, Richard Mather’s son Increase, and grandson Cotton, believed in Witchcraft. Both published books on the subject. These were Increase’s An Essay for the Recording of Illustrious Providences (1684) and Cotton’s Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions (1689). Increase’s book has been cited as the cause of the Salem Witch Trials:

Among his books is An Essay for the Recording of Illustrious Providences (1684), a compilation of stories showing the hand of Divine Providence in rescuing people from natural and supernatural disasters. Some historians suggest that this book conditioned the minds of the populace for the witchcraft hysteria of Salem in 1692. Despite the fact that Increase and Cotton Mather believed in witches—as did most of the world at the time—and that the guilty should be punished, they suspected that evidence could be faulty and justice might miscarry. Witches, like other criminals, were tried and sentenced to jail or the gallows by civil magistrates. The case against a suspect rested on “spectral evidence” (testimony of a victim of witchcraft that he or she had been attacked by a spectre bearing the appearance of someone the victim knew), which the Mathers distrusted because a witch could assume the form of an innocent person. When this type of evidence was finally thrown out of court at the insistence of the Mathers and other ministers, the whole affair came to an end.

Increase Mather, Puritan clergyman, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Here’s Cotton Mather on the same subject:

[D]o not lay more stress on pure spectral evidence than it will bear … It is very certain that the Devils have sometimes represented the Shapes of persons not only innocent, but also very virtuous. Though I believe that the just God then ordinarily provides a way for the speedy vindication of the persons thus abused.

Selected Letters of Cotton Mather. Baton Rouge: Kenneth Silverman, ed. (1971).

After the trials both Increase and Cotton published works that played down their involement in the trials.

Liverpool Witches in the same period

Liverpool had its own witches in this period. It even had its own ducking stool to prove their guilt. But one family of witches lived undisturbed by the authorities. You can read all about The Witches of Castle Street on my other website Bygone Liverpool, where we also discovered the exact location of their house.

Was the 1688 house really part of Rimmer’s Farm?

I have doubts whether this house was really part of Rimmer’s farm, so let’s look at the evidence. Robert Griffiths wrote in 1907:

“Rimmer’s”, a group of six buildings erected in 1688 in what is now Dingle Lane.

This was not entirely correct. Firstly, Griffiths had no idea when the other 5 of those buildings were erected, he based the date on the only surviving building, because that had a date stone. Secondly, the farm was reached by the path that later became Dingle Lane, but 4 of those buildings were located at the bottom of it, away from the other two.

On the 1768 map, the name Rimmer appears below cluster of four farm buildings. There’s another two buildings to the south (right) of Dingle Lane. The house bearing the date 1688 was actually one of two that were on the lane itself and had its entrance fronting it.

Later in his book, Griffiths even says that ‘the fields for some distance surrounding it being known as “Farm Fields”. This was true, but by 1754 Farm Fields was already on a different plot entirely from the other farm buildings, as it was on the other side of the lane.

As I mentioned earlier, I have redrawn the entire plan of Toxteth because it is hard to read. It also uses the long s (ſ) that looks like an f that can be confusing for those not used to reading 18th century text.

I’ll make the whole plan available as a free searchable pdf soon.

©Jim Kenny, Priory and the Cast Iron Shore.

Looking at the 1765 estate plan above, this is the same as the 1754 plan, so well before Yates and Perry’s map that Griffiths based his assumption on. It can be seen that Rimmer’s farm was on plot number 41, but the 1688 house was on plot number 40, between the fields named Barn Hey and Meadow (in the pink area). We can also see that instead of 4 buildings at the bottom of the lane there were actually 5 – this was Rimmer’s farm (between Green, Kiln Meadow and Slate Pit Hey in the green area).

What appears to be the main farmhouse of Rimmer’s, is within an orchard enclosure. Seen in this context, Rimmer’s looks like a completely separate farm to the 1688 house.

The 1786 map by William Yates looks similar to that in 1768 with 6 buildings, four of which surround the bottom of the lane. I have coloured the 1688 building red. Looking at simpler maps like this, without the plots indicated, it is understandable how the error arose. Note: This is a from a map of the whole of Lancashire so the level of detail is actually remarkable.

We can get more insight by comparing Lang’s map of 1754, the estate plan of 1765 and the Tithe map of 1847. As I mentioned, Lang’s map is really faded, but there is no trace of any buildings where Rimmer’s farm should be. The only house he drew was the one from 1688. In 1765 all the buildings are shown. But by 1847 all but the 1688 house have been demolished – ready for development.

Here is a close up of Lang’s map. I had to darken the area to enable the 1688 house to be seen more clearly. Darkening the area around Rimmer’s Farm still didn’t reveal any buildings. Lang must have thought they weren’t worthy of inclusion. He did however draw the orchard within the plantation, almost identically to the 1765 map. This close clearly shows that the house on a completely different plot of land to the farm.

Association with Rimmer’s Farm

The first person to associate this house with Rimmer’s Farm was almost certainly Griffiths in 1907. I can’t find a record of the house being associated with the farm before him.

The actual name of the house was Ivy Cottage. It had also been known as Yew Tree Cottage in this clipping from 1827, where someone is describing a visit to the Dingle. As the next house west described is West Dingle, this must be the 1688 house. (ignore the nonsense about King John).

From the small chapel at the bottom of the straight line road leading from the High Park, we turned to the right and pursued a lane leading to the west [Dingle Lane]…

…we observed a very ancient building, called Yew Tree Cottage, in the old irregular English style, with numerous gable ends and many chimneys, which serve for ornament as well as for use. The house stands in a garden orchard of considerable extent and has evidently been a place of importance in its better days. Indeed, the story goes that King John once found refuge for the night under its roof. There are still apparently some good apartments, but it is suffered to fall into decay. The front gate of this approach is built up, and the grounds have lost that neatness which they, no doubt, exhibited under its former master’s hand. Close to this is the wooded entrance to a stately stone mansion [West Dingle] on an eminence further west, the lawn from which slopes to the shore.

Sketches of Liverpool and the surrounding country. Liverpool Albion – Monday 09 July 1827

John Bostock first person to describe Hayfever

Perhaps Bostock’s lasting legacy is that in 1819 he was the first person to describe Hayfever, which he called ‘catarrhus aestivus’ or summer catarrh. Bostock knew the symptoms because he had suffered from it himself since the age of 8. In a paper he described a patient named JB, this was himself. He noted that the symptoms occurred each year ‘about the beginning or middle of June each year’. As Bostock lived at the rural Knot’s Hole, this must have added to his symptoms.

From about the age of 8 and in about the beginning or middle of June each year JB suffered the following symptoms: a sensation of heat and fullness in the eyes, first along the edges of the lids, and especially in the inner angles, but after some time over the whole of the eyeball; a slight degree of redness in the eyes and a discharge of tears; worsening of this state until there was intense itching and smarting, inflammation, and discharge of a very copious thick mucous fluid. To these symptoms were added sneezing, tightness of the chest and difficulty in breathing, with irritation of the fauces and trachea.

John Bostock’s first description of hayfever. Manoj Ramachandran and Jeffrey K Aronson

It is very interesting to note that the person credited as discovering the link of sugar to Diabetes was also a resident of Toxteth Park. See Miscellaneous notes at the end of the post.

Diabetes also first discovered in Toxteth Park

It is very interesting to note that the person credited as discovering the link of sugar to Diabetes was also a resident of Toxteth Park. This was Matthew Dobson (born 1732). His practise was a 4 Harrington Street but he lived in Toxteth Park. In 1772 Dawson had a 33 year old patient called Peter Dickonson who was passing 28 pints of urine every 24 hours. Dobson had another 8 patients with the same complaint. Dawson evaporated his urine and recovered a cake of sugar. By this, Dobson proved the sweetness in his urine and blood came from sugar (hyperglycaemia).

Don’t read this if you’re eating – Dobson did this by tasting the sugar cake:

There remained after the evaporation, a white cake … This cake was granulated and broke easily between the fingers, it smelled sweet like brown sugar, neither could it, by the taste, be distinguished from sugar except that the sweetness left a slight sense of coolness on the palate.

The Annual Register, Or, A View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year 1776

Matthew Dobson’s surgery in Liverpool was at 4 Harrington Street.

The modern location is 7 Harrington Street. Amazingly, there are no plaques in Liverpool marking the huge scientific achievements made by either Dobson or Bostock.

There are two Dobson memorials in the Ancient Chapel of Toxteth. One is to Matthew, another is a touching remembrance of his daughter Eliza. Eliza died in 1778 aged just 17. It is in Latin but here is a translation:

She is dead

My beloved daughter,

Elisa,

My pretty, winsome, kind-hearted

daughter is dead.

Very simple she was and withal very intelligent,

accomplished and well-read,

pure in heart and spiritually minded,

and she is dead.

Farewell, dear Elisa, farewell !

Always will you be regretted by your grieving father;

regretted but, thanks be to God,

not lost to me,

for a happier day will dawn

when I shall see you again, my daughter,

and live with you for ever and ever.

Matthew Dobson to his dear sweet and blessed daughter Elisa,

who, at the age of seventeen and in the year of our Lord 1778,

departed peacefully to heaven.

Matthew Dobson moved to Bath soon after his daughter’s death. He died there in 1784.

Unfortunately no picture of Mathew Dobson exists. Apparently his portrait used to hang in Liverpool Infirmary but this was badly damaged by a mischievous house surgeon with a pea-shooter in 1874 and was lost.

Mathew Dobson of Liverpool (1735-1784) and the history of diabetes

Future posts on the Dingle

The next post will cover the period from the early 19th century up to present day. This will focus on the two famous families who built their homes here, the Yates and the Croppers.

Further reading:

For more information about the earliest history of Toxteth Park, read my post Discovered: The ancient boundaries of Toxteth Park. I’ve included a route map so you can follow in the footsteps of 13th century knights who originally marked its boundaries. Spoiler: You’ll be walking considerably further than what you see on the Tithe map.

I recommend this Yo! Liverpool Forum post from 2009. Here you’ll find some of the images from Liverpool Office I have shared here, plus information about the modern location of Knott’s Hole.

This post The Dingle: Digging into The Past borrows from the Yo! Liverpool post but also has different information, images and insights. The focus on this post is the modern site of the dell of the Dingle at the allotments – highly recommended.

Another great Dingle post is by Martin at Historic Liverpool. There’s also a history of Toxteth by Martin that I recommend.

Copyright notice:

Copyright of original archive images belongs to those named below the images. All original research, photographs taken by myself, illustrations, artists impressions, and archive images and maps that have notes added are all ©Jim Kenny. Permission to share is only granted if the site is credited and a link provided.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to show your appreciation, you can Buy me a coffee. This will give me £5 to help me fund my research and continue this website. If you can afford it, you can buy me as many as you like. I’ve got plenty more posts to come. Some of these contain some very important discoveries.

Just click on the logo below.

3 thoughts on “A history of the Dingle, Part Two: From the earliest records to the 18th century”