I originally posted this on my other website Bygone Liverpool that was a collaboration. Now that project has finished, it is far better suited to join my other research on Toxteth Park.

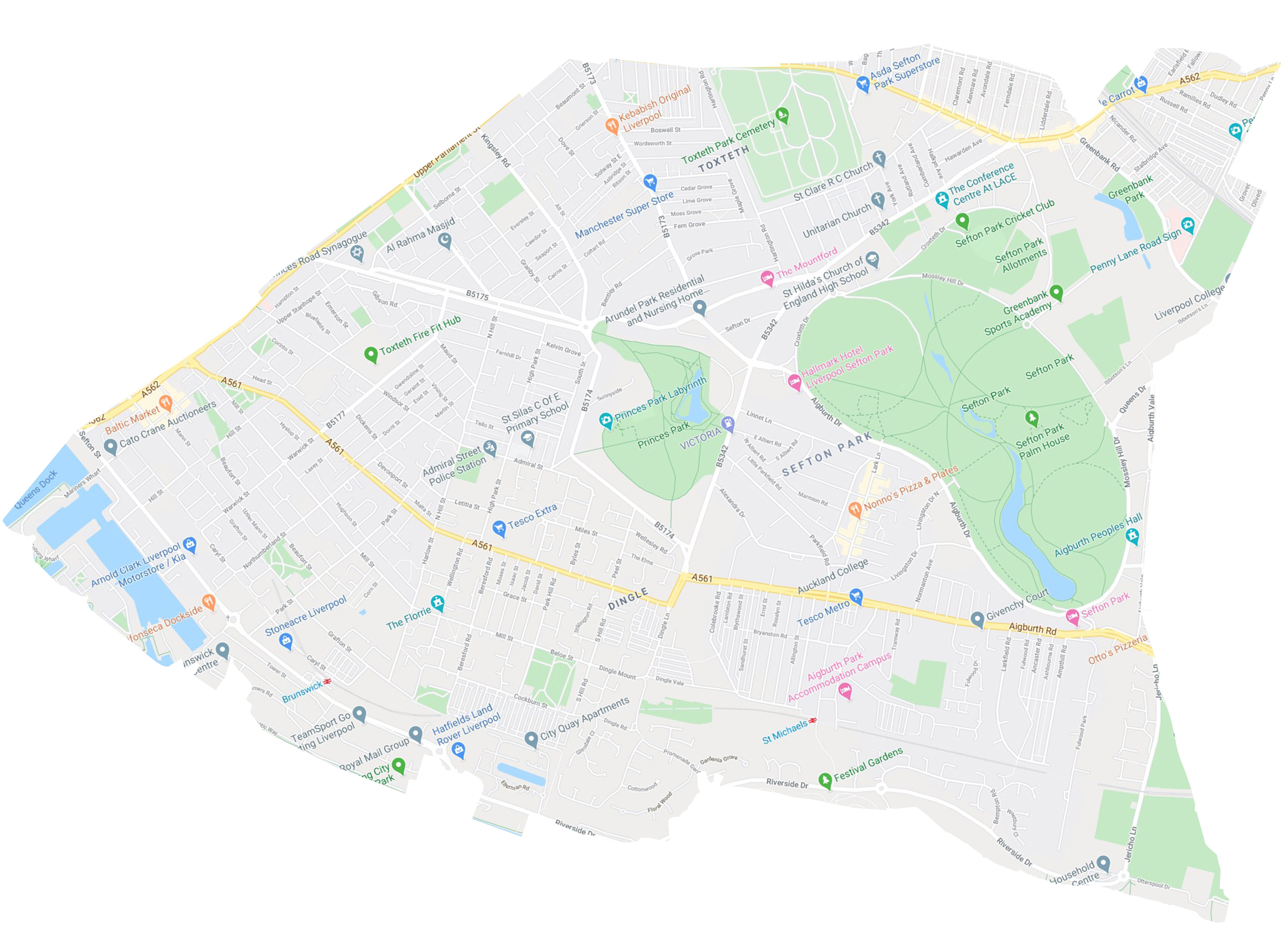

In this post I attempt to rediscover the earliest boundaries of Toxteth Park using documents from the 11th to 14th centuries. I’ll show that half of Liverpool city centre was originally in Toxteth. I’ll also look at the origin of Everton, its name and its original boundary.

This was without doubt my most complex post so far, but please stick with me as I give you a tour around Toxteth Park in 1228. Our tour guides will be twelve knights from the reign of Henry III who were ordered to mark the park’s boundary. Bring sandwiches and wear comfy shoes, we’ll be travelling much further than you expect.

For anyone feeling energetic, I’ll show how you can follow the exact route yourself. I’ve mapped out the boundaries and added them as street directions, these can be found at the end of this post in Miscellaneous notes.

Featured image: Based on an original line illustration:- ‘Hunting in Toxteth Park, Time of King John’. One of the superb illustrations by Joshua Fisher – commissioned by Robert Griffiths to illustrate his 1907 history of Toxteth Park. ©Jim Kenny

Where is Toxteth, exactly?

It may seem an odd question to start off a post about locating ancient boundaries, but the problem is that even the present location of what remains of this once large and historically important area is disputed.

The administration page for the Wikipedia’s Toxteth entry has a whole debate on where the area is, this is mainly to clarify the distinction between modern ‘Toxteth’, and its ancient predecessor ‘Toxteth Park’.

In 2019 Lisa Rand of the Liverpool Echo wrote a piece entitled ‘We try to find out where exactly is Toxteth – One of Liverpool’s most famous areas has a long history – but people are divided as to where Toxteth is’. In particular, the article debates whether Dingle is part of Toxteth:-

The overwhelming consensus from a straw poll of a dozen people is that Dingle is not part of Toxteth, and that Park Road marks the boundary between the two places.

On Park Road, however, the boundary line becomes much less clear. Of more than a dozen people asked on both sides of Park Road, there was an even split between those who believed Park Road was in Dingle and those who believed it was in Toxteth.

www.liverpoolecho.co.uk

Neither Dingle or Toxteth exist as electoral wards, and the boundaries of neither are recognized by the council – even though a search for it on the council’s website brings up many results. This from the same article:-

A spokesperson from Liverpool City Council confirmed “there are currently no official boundaries for Toxteth and Dingle.”

www.liverpoolecho.co.uk

At the time of writing (July 2022), proposals were being discussed to reshape Liverpool’s electoral map, and rename some of the wards. As of the 13th June 2022, Toxteth Ward has returned.

More confusion (sorry)

The original ‘Toxteth Park’ was such a massive area (from Upper Parliament Street to Otterspool) that more localised names were required for the tens of thousands of new residents who arrived when the terraced houses were erected (circa 1880s). Many of these names were geographically incorrect but stuck. For example, anyone living in any of the streets off Aigburth Road (southwards from the Dingle), was generally classed as living in Aigburth.

A street sign at end of Ullet Road, near the junction of Aigburth Road and Dingle, instructs us that Aigburth is 1¼ miles away.

Another street sign shown below is at Ashfield Road, in front is Jericho Lane leading to Otterspool. Aigburth is reached by turning left towards Garston. The name of the area to the right, and as far as Dingle, is anyone’s guess and is just referred to as the way to the City Centre.

Rather than being Aigburth, the land between Aigburth Vale and Dingle was originally part of Toxteth Park, Aigburth didn’t start until south of Aigburth Vale, and it still doesn’t (despite what estate agents may tell you).

I was born in Bryanston Road in 1964 and has Toxteth Park South on his birth certificate. The Toxteth branch of Martin’s Bank, on the corner of Chetwynd Street (opposite Lark Lane) was so called after 1966, and possibly well into the 1970s.

Political rather than geographic boundaries

Bacon’s map of 1885 places the centre of Toxteth Park at St. Michaels Hamlet.

Image via https://liverpool1207blog.wordpress.com/old-liverpool-maps/

But another map of of the same period shows the area of Toxteth Park divided into wards, South Toxteth can be seen between Brunswick and Dingle.

This can be explained by a change in how the wards were designated before 1895:-

The former wards within the borough of Liverpool, down to 1895, were called North and South Toxteth. On the inclusion of the rest of the township in 1895 an entirely new arrangement of wards was made; five wards, since increased to six, having been formed, each having an alderman and three councillors.

Townships: Toxteth Park, 1907, British History Online

Incorporated into Liverpool

Most of South Liverpool was outside the boundaries of Liverpool until the 19th century, and in the case of Garston and Aigburth, the 20th century. The northern (and more densely populated) part of Toxteth Park had been taken within the borough of Liverpool in 1835 with the remainder in 1895.

In 1974, our 900 year relationship with Lancashire ended when Liverpool became a borough of the new metropolitan county of Merseyside.

1981, Toxteth is the national newspapers

In 1981, rising tensions between (mostly Black) residents of the Granby area and the police erupted into what the national news media called the ‘Toxteth Riots‘ (or Uprising from the participants point of view). This brought the name Toxteth into the international spotlight and came to define in many peoples’ minds where the area actually was.

Prior to 1981, few residents of the Granby Ward had referred to their area as Toxteth – perhaps with the exception of some older residents. Because of this, it is often claimed that it was out-of-town (sometimes specifically London) journalists covering the story who saw a Toxteth street sign (below) and coined the term the ‘Toxteth Riots’.

The ‘Toxteth Riots’ began on the weekend of Friday 3rd July. On the Saturday, the weekend edition of the Liverpool Echo (Weekend Echo, July 4/5 1981) reported the appearance of Leroy Cooper in the Magistrates’ Court earlier that day. The Echo used ‘Toxteth’ twice in this front page article, they said the arrest followed ‘incidents in the city’s Toxteth area last night’.

Following the weekend, the national daily newspapers also then named the area as Toxteth. One Monday 6th July, one national newspaper reported that ‘The Violence flared as mobs ran riot in Liverpool’s Toxteth district’. On the same day the Mirror’s front page had an image of police with riot shields with the caption ‘FLASHPOINT: Police at Toxteth are attacked by a petrol bomb’.

A search on the British Newspaper Archive from 1980 to July 3rd 1981 shows that the Liverpool Echo referred to the area around Granby Street as Toxteth hundreds of times – it seems the term was coined by Liverpool Echo journalists after all.

Liverpool Echo – Wednesday 03 June 1981. British Newspaper Archive.

Liverpool Echo – Tuesday 07 July 1981. British Newspaper Archive.

After the ‘Toxteth Riots’, the area of Toxteth was then mostly associated with the streets bounded by Upper Parliament Street, Lodge Lane and Sefton Park Road, and Princes Road and Croxteth Road. This is sometimes referred to as the Granby Triangle.

For more information about how the perceived area of the Dingle has also changed, see ‘Dingle in the late 19th and early 20th centuries’ in Miscellaneous notes.

The original Toxteth Park

Now I have shown the distinction between the modern day Toxteth and the historical Toxteth Park, we can now go much further back in time.

Toxteth had been an ancient woodland that existed long before the Norman invasion of England in 1066. It covered a considerable area of (what would later be) South Liverpool.

It became Toxteth ‘Park’ when King John took it as one of his royal hunting grounds after 1207 (although there is no evidence he ever used it himself). Most of the area remained rural well into the 19th century with many of its terraced houses dating after the 1880s.

The 18th to 19th century boundaries of Toxteth Park

If there is confusion as to the location of modern Toxteth, at least we know exactly where Toxteth Park was from at least the 18th century.

Toxteth Park covered a great area of what is now south Liverpool. If it is imagined as a box the bottom would be the Mersey, the top Smithdown Road, the left side Parliament/Upper Parliament Street and the right side would be Penny Lane down to Otterspool Park.

Toxteth Park before the Norman Conquest

To fully appreciate the history of the area, we have to go back almost 1,000 years – before Lancashire even existed – before the Norman invasion of Britain in 1066.

The landscape of Liverpool and Toxteth Park was dominated by water – The Mersey of course, the ‘Pool’ of Liverpool, the stream that later fed ‘Mather’s Dam’, the Dingle, Dickenson’s Dingle met the Mersey at St. Michael’s Hamlet. That was used to create Prince’s Park lake. In the south east are also the Upper and Lower Brooks that were used to form Sefton Park Lake. After these two brooks joined, they formed the ‘River Jordan’ and run underground at Aigburth Vale and then to the Mersey at Otterspool.

Even today, these water courses (apart from the Mather’s Dam stream) can be seen using LiDAR. Despite hundreds of years of extensive developments, the Pool that gave Liverpool its name (filled-in to make the wet dock in 1710) can still be made out – being the darker crescent shape to the right of the text:-

The Domesday Book

William, Duke of Normandy conquered Britain on 14 October 1066 by defeating King Harold at the Battle of Hastings, he was crowned King William on Christmas day that year. 23 years after the conquest, the King and his council met at Gloucester where William ordered a great survey of England and parts of Wales.

This ‘Domesday Book’ also shows who had the land before the conquest. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded the event:

After this the king had important deliberations and exhaustive discussions with his council about this land and how it was peopled, and with what sort of men. Then he sent his men all over England into every shire to ascertain how many hundreds of ‘hides’ of land there were in each shire. He also had it recorded how much land his archbishops had, and his diocesan bishops, his abbots and his earls, and – though I may be going into too great detail – and what or how much each man who was a landholder here in England had in land or live-stock, and how much money it was worth. So very thoroughly did he have the inquiry carried out that there was not a single ‘hide,’ not one virgate of land, not even – it is shameful to record it, but it did not seem shameful for him to do – not even one ox, nor one cow, nor one pig which escaped notice in his survey. And all the surveys were subsequently brought to him.

A young Norman aristocrat named Roger de Poitou (Poitevin) had been granted huge areas of land across England. Born in 1058, Roger was only 27 when the Domesday Book was commissioned. Roger’s father was one of William the Conqueror’s principal counsellors at the time of the conquest of England.

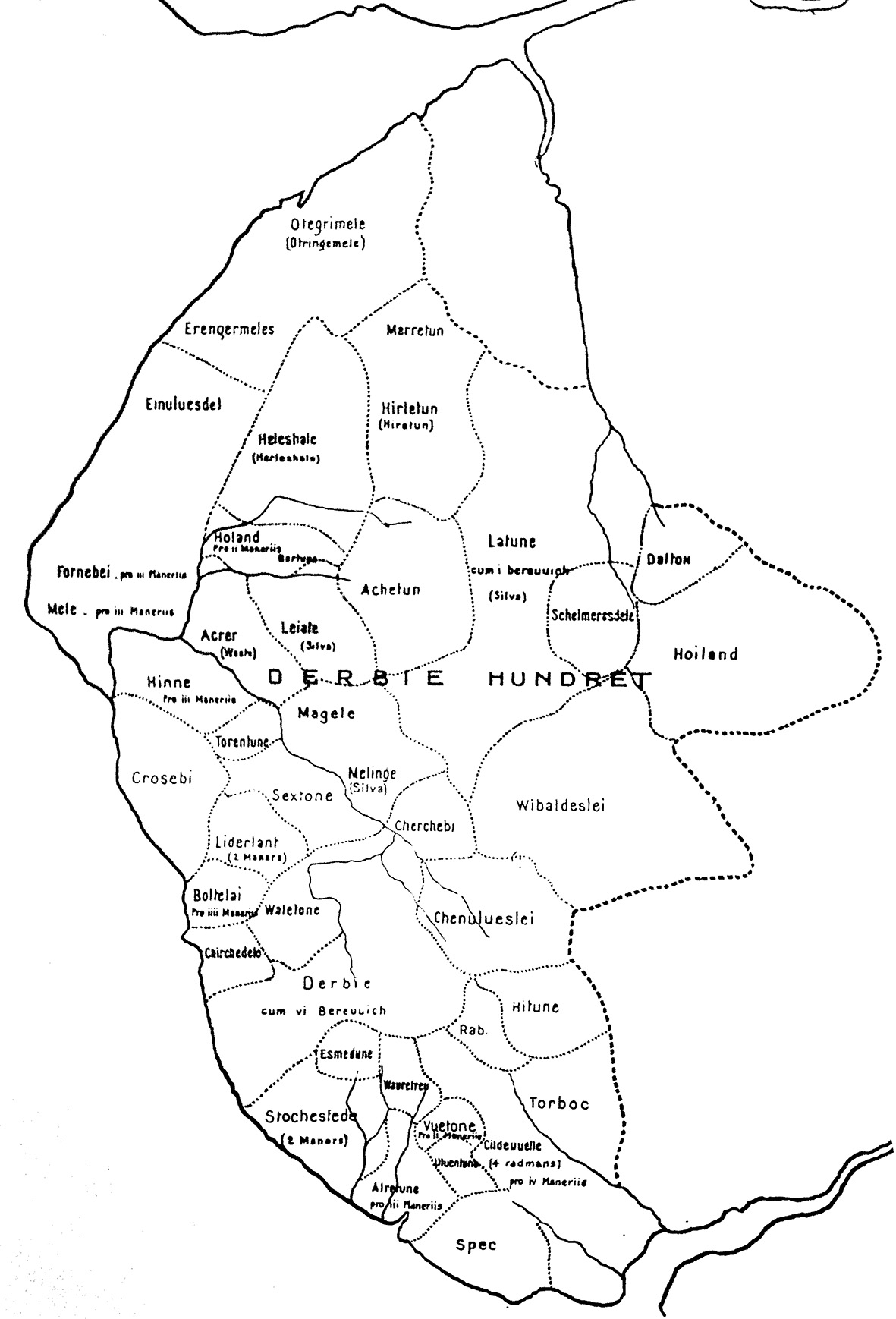

The beginning of Lancashire

Roger became lord of all the land ‘inter Mersam et Ripam’, meaning ‘between the Mersey and the Ribble’ – this was to become Lancashire. You can read the full list of land owned by Roger de Poitou here: opendomesday.org

No mention of Liverpool in the Domesday Book

In what is now known as South Liverpool, the following are listed: Toxteth (Stochestede), Smithdown (Esmedune), Wavertree (Wauretreu), Woolton (Uluentune), Allerton (Alretune), Childwall (Cileuuelle) and Speke (Spec). You can read the full list of Merseyside places here.

However, there is no mention of Liverpool itself. To account for Liverpool’s exclusion, some historians (out of desperation) have suggested that Liverpool was situated within an area mentioned in the Domesday Book called ‘Esmedune‘ (Smithdown), that King John later added to Toxteth Park:-

Every one knows that amongst these manors Liverpool is not mentioned, or at least only appears under the name of Esmedune or Smithdown, a place mentioned in documents of the 13th century in connection sometimes with Toxteth and sometimes with the forest of West Derby. Four hundred years later, we find receivers appointed for the crown-rents of Toxteth, Smithdown Moss, and Liverpool : and the name is still perpetuated in Smithdown Road, that runs towards Liverpool along the boundary of the townships of Toxteth and West Derby.

Smithdown then probably lay west of Derby and north of Toxteth, and contiguous to both, and therefore occupied the site of, at any rate, a considerable portion of Liverpool, which latter name was perhaps confined at the time of Domesday to the well-known pool or inlet of the Mersey, now built over, answering to Wallasey Pool on the opposite side of the river.

THE DOMESDAY RECORD OF THE LAND BETWEEN RIBBLE AND MERSEY, Andrew E. P. Gray, M.A., F.S.A., 1887

Mr. Gray may have been certain Liverpool was part of Esmedune, but he was completely wrong (we’ll show where Esmedune was later).

Mr. Bawdwen, in his translation of Domesday, has appropriated Esmedune, or Smedone, to Liverpool ; but this adaptation is not remarkably felicitous ; for a place in Toxteth was denominated Smithden, from the reign of king John to that of Charles I.

History of the county palatine and duchy of Lancaster, Edward Baines, 1836

The exclusion of Liverpool does not mean it didn’t exist in 1086. The Anglo-Saxon’s Chronicle’s claim that ‘not even one ox, nor one cow, nor one pig which escaped notice in his survey‘ was in fact false. Areas including London, Winchester, Bristol, Northumberland and Durham were left out, as was large areas of Sussex and Wales.

Mr. Bawdwen, in his translation of Domesday, has appropriated Esmedune, or Smedone, to Liverpool ; but this adaptation is not remarkably felicitous ; for a place in Toxteth was denominated Smithden, from the reign of king John to that of Charles I.

History of the county palatine and duchy of Lancaster, Edward Baines, 1836

It wasn’t necessary for some past historians to try and explain Liverpool’s omission by ‘appropriating’ Esmedune. Mike Royden, in his excellent book Tales from the Pool provides a more likely explanation:-

Although Liverpool is not named in Domesday, it is thought to have been one of the six unnamed berewicks (barley farms) or ‘outliers’ belonging to this superior royal manor of West Derby. Once the named local areas in Domesday are accounted for, there are several omissions which have Saxon or Norse origins and would, therefore, be expected to feature. These sites were most likely the six outliers held by Edward the Confessor in 1066 which were directly dependant on the West Derby estate, and probably included Thingwall, Garston, Aigburth, Hale/Halewood, Everton and the fishing hamlet at Liverpool.

Tales from the Pool, Mike Royden, 2017

For more information on areas left out of the Domesday book, see also ‘Errors and omissions’ here.

Toxteth held by Bernulf and Stainulf

Toxteth was listed as ‘Stochestede’ in the Domesday Book – a ‘stockaded place’ derived from the wooden wall (later stone) that surrounded its perimeter. Evidence for this wall comes from a pipe roll dated 1228-30 when a warrant was given for a new stone wall to be built around the park. The later stone wall had one of its gates near St James Church, near the old boundary of Liverpool and Toxteth Park – Parliament Street.

Toxteth’s stockade was likely built to keep the deer in, but would have the added benefite of keeping poachers out:-

In medieval and Early Modern England, Wales and Ireland, a deer park (Latin: novale cervorum, campus cervorum) was an enclosed area containing deer. It was bounded by a ditch and bank with a wooden park pale on top of the bank, or by a stone or brick wall. The ditch was on the inside increasing the effective height. Some parks had deer “leaps”, where there was an external ramp and the inner ditch was constructed on a grander scale, thus allowing deer to enter the park but preventing them from leaving.

Deer park, Wikipedia

See also ‘A Deer Park in Sefton Park’ in Miscellaneous notes

The Domesday book also gives us a glimpse of Toxteth Park before the Norman invasion. It was then divided equally in two parts by two Saxon Thanes named Bernulf and Stainulf:

Bernulf held Stochestede (Toxteth).

There was one virgate of land and half a plough: it paid four shillings.Stainulf held Stochestede (Toxteth).

There is one virgate of land and half a carucate or ploughland: it was worth four shillings.

If it is the same person, prior to the invasion, Stainulf (Stenulf, meaning Stone Wolf) was himself was Lord of large areas of land across England. A Stainulf is listed 30 times in all, from Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Yorkshire and Cheshire. After the conquest his name is associated with only two, as being Tenant-in-Chief at Calow in Derbyshire and Tittensor in Staffordshire. Bernulf (Bernwolf, meaning Bear Wolf) was associated with 42 places before the conquest, and only 11 after.

Roger de Poitou granted to Robert de Molyneux the areas around Sefton. The powerful Molyneux family would later hold Toxteth and their ownership would be key to the park’s history. Sefton Park (opened in 1872) owes it’s name to the family who had become ‘Earls of Sefton’ in 1771.

Ancient Smithdown

Esmedune, (‘Smedune – meaning ‘smooth down’, evolved into Smeatham and finally into Smithdown), is listed as previously being under Aethelmund, this area would later be incorporated into Toxteth Park by King John.

It was called the Earl’s Smetheden in the reign of Edward I., when it was held in alms of the officers of Edmund, earl of Lancaster, to whom then belonged the manor of “Liverpole,” with the passage of the Mersey.

The use of Smeatham Lane continued until at least 1841. The clipping below reported the death of Mrs. Coyle, relict of the late Henry Coyle of the Brook-house.

Esmedune is said to have included the Moss Lake and the Turbary (turf – peat bog) that the town of Liverpool would later have a right to (from 1309/10). The Moss was critical to Liverpool as it was a source for peat but also the watercourse that ran from it. This ‘Moss Lake’ provided the town with much needed fresh water at ‘The Fall Well’. Ownership of this land was disputed in the 17th Century when both Edward Moore (of Liverpool) and Lord Molyneux (owned Toxteth Park) both laid claim to it. (see later in this post)

The exact location of Esmedune was previously unknown (see later in the post), part of it was cultivated as can be seen from the Domesday Book entry.

George Chandler, in his history of Liverpool published in 1957, has two maps of the area. Confusingly, Chandler places Esmedune in different locations on each! His 1086 Domesday Liverpool map differs greatly to his conjectural map that has ‘Esmeduna Moss’ spanning the entire distance from Toxteth Park to ‘The Pool’ that gave Liverpool its name.

Chandler reproduced this map from this 1900 HSLC paper by J. H. Lumby.

On this conjectural map, Toxteth Park is shown as Stochestede. Lumby has assumed the area Esmedune (Smithdown) was northeast of Toxteth. This would be incorporated into the park by King John. Although ancient, most of the place names are still reconisable today; Spec – Speke, Hitune – Huyton, Waletone – Walton, Cildeuuelle – Childwall, Sextone – Sefton etc.

If Chandler’s second map above is correct, showing Esmedune covering the entire Heath and Moss, it raises a big question:-

As we know Esmedune was added to Toxteth Park by King John, doesn’t that mean Toxteth Park originally cover this whole area? If so it would be half of Liverpool city centre and beyond.

1207, King John grants Liverpool its Charter and takes Toxteth Park

Although Liverpool at this point was just a small coastal village, King John saw its potential as an embarkation point for Ireland (he was also Lord of Ireland from 1199 to 1216).

John ruled in England from 1199 to 1216, but in Ireland for more than twice as long. First nominated as Ireland’s future governor in 1177, he commanded military expeditions there in 1185 and 1210.

King John: the making of a medieval monster

Writing in 1907, Robert Griffiths recorded the momentous event in the history of Liverpool when King John (1166 – 1216) issued his Royal Charter:

On August 23rd, 1207, the ninth year of the reign of King John, the King confirmed to Henry FitzWarine a grant of several manors which had been made by his father Warine de Lancaster, the father of Henry FitzWarine ; but at the same time reserved to himself the Manor of Liverpool, which had been one of the manors originally granted to Warine de Lancaster by King Henry II, and substituted for it another manor named English Lea, situated in the neighbourhood of Preston. By this arrangement King John became possessor of the Manor of Liverpool, which, five days later, he proceeded to form into a borough and seaport by a grant of extensive privileges.

The King encouraged people to settle in Liverpool, giving them ‘all liberties and free customs’. About 168 burgages (rented properties owned by a King or Lord) were soon taken.

For his court’s recreation, King John took advantage of the woodland in the neighbourhood. The King increased the size of Toxteth Park by taking Esmedune from ‘a poor man’ named Richard son of Thurstan. In exchange, the King gave Richard Thingwall (see also Thingwall Hall, Knotty Ash).

In a move similar to the later Highland Clearances, the original farming occupants of Toxteth Park were removed, and it is presumed they then settled in the new town of Liverpool.

Image: British Library

Did King John ever use Liverpool to travel to Ireland?

The King made two expeditions to Ireland and landed at Waterford for both. The first was before the charter (1185). The second was 3 years after. When he returned to Ireland in 1210 he sailed from South Wales and not Liverpool. Landing at Crooke, John’s preference of South Wales over Liverpool was likely based on the proximity of South Wales to Waterford.

The Master Forester of Toxteth park

In 1207, the keeper of Toxteth Park was William Gernet, he had inherited the position from his father Benedict – before the time of King John:

In 1207 when William Gernet had livery of the master forestership in succession to his father Benedict, the covert of Toxteth and the arable lands belonging to the underwood of the forest—probably in the vill of West Derby—were excepted, so that, no doubt, these had already separate custodians.

www.british-history.ac.uk Toxteth Park

Another pipe roll of 1210 show that, just three years after King John’s charter, the Master Forester of Toxteth Park had, what Chandler refers to as, a ‘considerable hunting establishment.’ This consisted of:

4 master huntsmen and 49 men, 10 horses, 2 packs of dogs, 52 spaniels, 2,000 hand nets and 260 cocks.

1210 Pipe Rolls, 13 John, 1210-11, Roll 57, m.id.

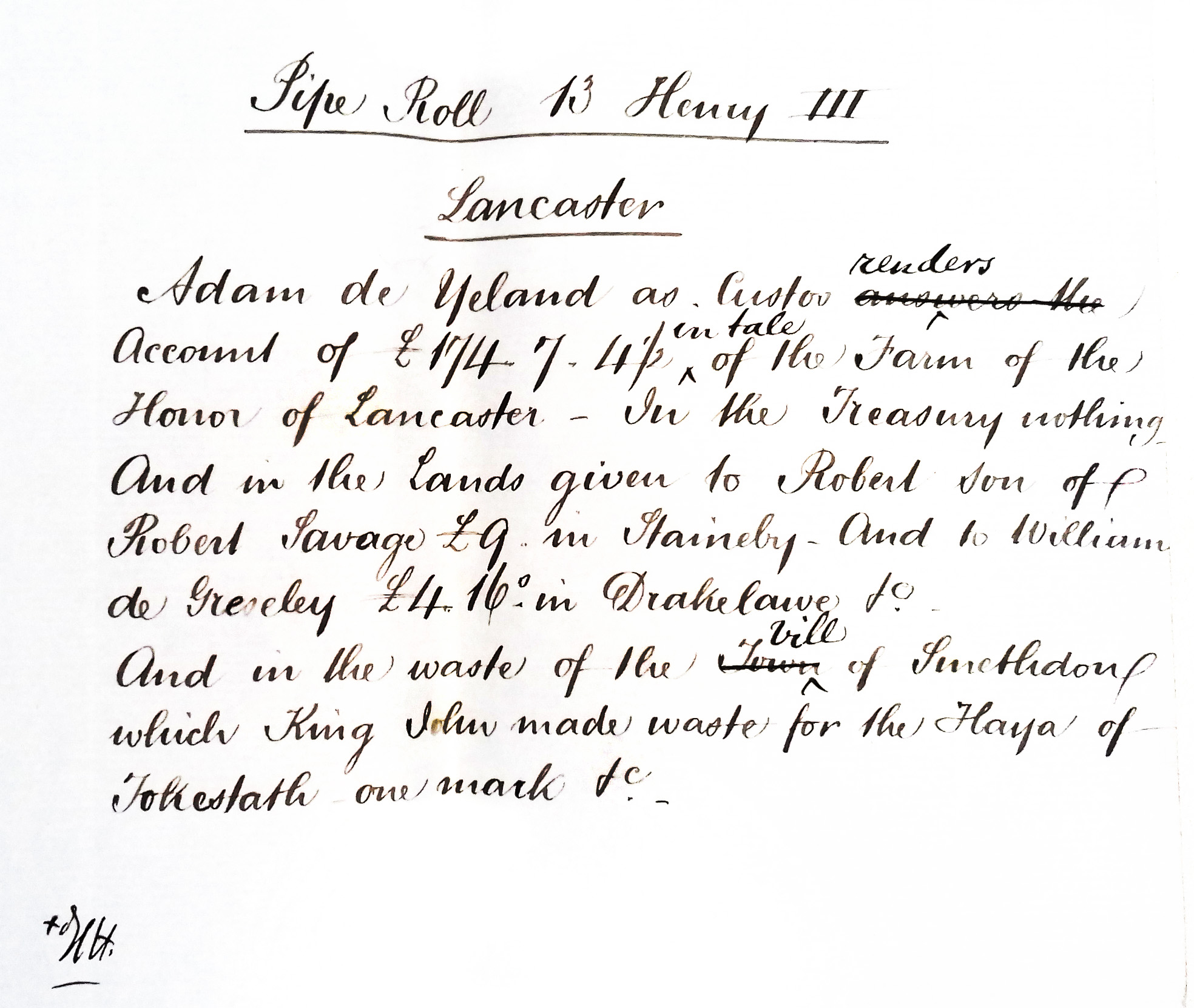

Toxteth Park under King John’s son, Henry III

A pipe roll made during the reign of King John’s son, Henry III (1207 – 1272), mentions that John had declared the vill of Smithdown ‘waste for the Haya (Hey – field) of Tokestath’ and valued it at one mark. This shows that at least one part of Toxteth Park was cultivated.

Deer in Toxteth Park belonging King John’s grandson

A record from 1275 shows that Roger le Strange, of Ellesmere was allowed to take ten Harts (deer) from Toxteth Park. At this point Toxteth belonging to the King Edward I‘s younger brother Edmund. Edward and Edmund were grandchildren of King John.

In 1275 the Justiciar of Chester was ordered to allow Le Strange to take two stags in the forest of Wirral, which were to be salted and brought to Westminster for the King’s use at Michaelmas, a similar order to the sheriff of Lancashire permitting ten harts to be taken in the King’s brother’s chace of Liverpool, i.e. Toxteth Park, then in the hands of Edmund of Lancaster.

THE ROYAL MANOR AND PARK OF SHOTWICK, Ronald Stewart-Brown, M.A., F.S.A, 1912. HSLC

For more information on King Edward’s and Edmund’s connection to Toxteth see below: Toxteth oaks used in Edward I’s Welsh castles.

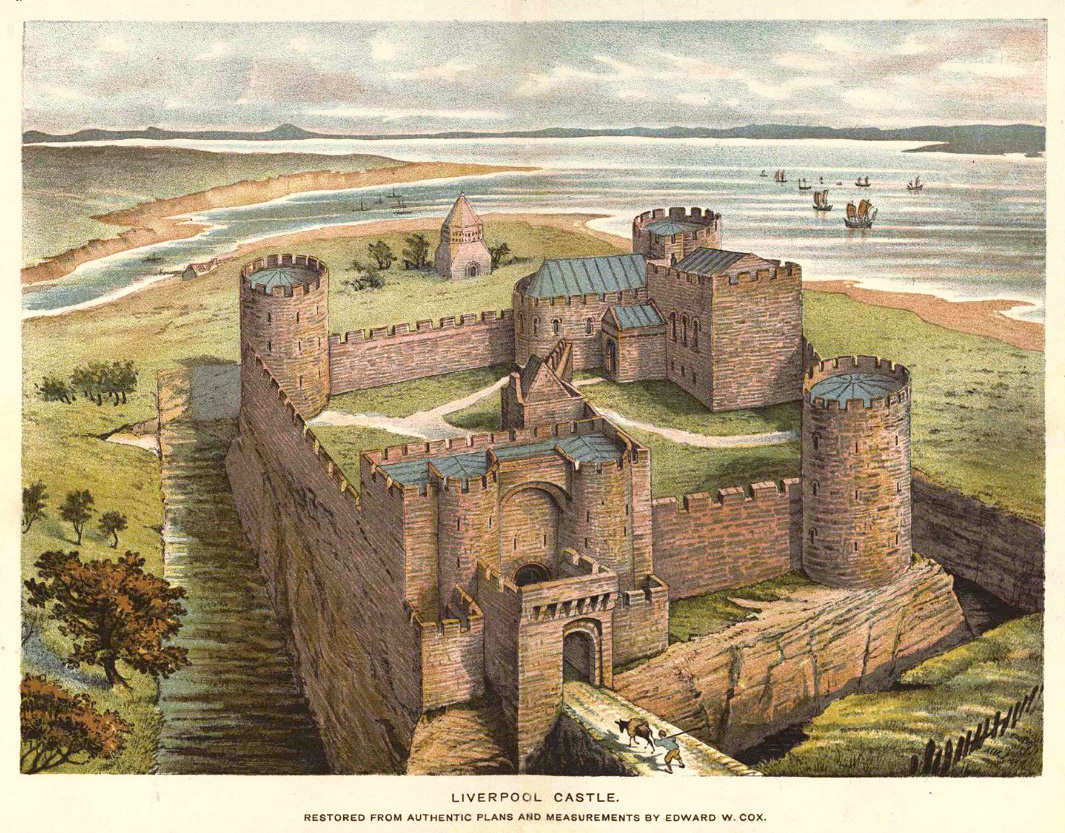

Liverpool castle, overlooking Toxteth Park

It is often said that it was King John himself who ordered the building of Liverpool Castle. It is likely that an earlier fortification preceded it, as Chandler stated in 1957 ‘a fortified manor house may have existed before the creation of the borough’.

The building of the stone castle was completed in the 1230s – 20 years after the death of John, probably by William II de Ferrers, the 4th Earl of Derby in 1232.

Mike Royden explains that the date for the commencement of the building ‘has long been a matter of contention, since very little documentary evidence exists’, he then provides a useful summary:-

To summarise, John probably had plans for a castle but did not live to see construction begin. Efforts were made sometime after 1226 to clear an adequate site, although work is unlikely to have commenced until Henry off-loaded his Crown lands in Liverpool in 1229. (Randle Earl of Chester held them until his death in 1232). When in the hands of William, Earl of Ferrers in 1232, work was begun but it was decided there were shortcomings in the defensive structure and he was directed in 1235 to strengthen it, with the total work being completed by 1237.

Tales from the Pool, Mike Royden, 2017

From the online archives of The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire 42-11-Cox.pdf

The castle was situated on the site of the Queen Victoria monument, the bridge in front led to Castle Street. Behind the castle can be seen the Pool that gave the town its name, and beyond that was the path to Toxteth Park.

Of the castles position overlooking Toxteth Park, Chandler wrote:

Even the huntsman in Toxteth Park beyond the pool of Liverpool must often have delighted to see the postern towers framed in the foliage as he chased deer. Few castles can have been visible from such different points – sea, market, commanding ridge, forest, harbour and stream. No wonder Liverpool chose as its motto Deus nobis otia fecit – God has created these pleasures for us.

Map: Liverpool 1207, Old maps

Toxteth oaks used in Edward I’s Welsh castles

Griffiths and most other historians state that Toxteth was disparked in 1591, sometimes the day given is 1604 (Griffiths was out by at least 5 years – see section Toxteth is disparked and Puritan settlers move in). ‘Disparked’ relates to it’s status changing from private land owned by the Lord, into land leased by farmers. As for the forest, there is evidence that much of it may have been cut down as much as 300 years earlier.

Liverpool and Toxteth Park had been granted to William II de Ferrers, the 4th Earl of Derby in 1232. William had been a favourite of King John (the same William that built Liverpool castle). When William died in 1247, his son (also William) inherited both Liverpool Castle and the earlier West Derby Castle. When the heir to the title, Robert de Ferrers rebelled against King Henry III, his lands and title were removed and taken back by the Crown. King Henry III then presented the land, along with Lancaster, to his second son Edmund Crouchback. Edmund was the younger brother of Edward (Longshanks) I (1272–1307). The nickname Crouchback may have come from ‘Cross back’ worn during the Crusades.

At this time King Edward was in the process of building his network of castles to subjugate the Welsh. The first castle to be built in Wales was Flint. King Edward looked to his brother to help supply the vast amount of timber required to build the castle. Although built of stone, It would still require a huge supply of wood for its construction. As well as scaffolding and timber-framed buildings within its walls, it had a motte and bailey. It also possibly had a wooden pallasade wall as a temporary defensive measure:

Stocks of wood-cutting, clearing and digging tools were being accumalated at Chester before the King’s arrival and after it lime was brought and sent ‘to the castle of Flint for the works of the said castle by the King’s command’. Before the end of July timber was being felled in the forests of Toxteth and Cheshire specifically for the construction of the new castle.

A. J Taylor, The Welsh Castles of Edward I. Hambledon Press, 1986

As well as Flint Castle, Edmund supervised the construction of Aberystwyth Castle in 1281, his Toxteth Park oaks were probably used again.

The place of many oaks

The story of Toxteth’s forest is linked to its neighbour Aigburth which name derives from ‘Ackeberth’ (oak place). Amazingly an oak tree survives that may have been standing when Edmund Crouchback ordered the felling of thousands of trees. The Allerton Oak in nearby Calderstones Park is possibly up to 1,000 years old, if so it may have been a spapling during the Norman invasion, and was already over 200 years old when it escaped Crouchback’s axe!

In 2019 this much loved tree was nominated and won the title of Tree of the year UK. It then went on to be nominated for European Tree of the Year and came 7th.

Toxteth park from 1446 to 1900

Toxteth is disparked and Puritan settlers move in

The history of the park is tied to two of the regions most powerful families and landowners, the Stanleys and Molyneuxs. The two royal parks, Croxteth and Toxteth, together with Simons Wood, were granted to Sir Richard Molyneux by the office of the Chief Forester of the Wapentake of West Derby, by King Henry VI, in 1446.

In 1447 Sir Thomas Stanley (1st Earl of Derby) came into possession of Toxteth Park. It was to stay within the Stanley family until 1596, when it was sold by William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, to Edmund Smolte and Edward Aspinwall.

In 1604 Smolte and Aspinwall then acted as agents in the sale to Richard Molyneux of Sefton (1594–1636) at a cost of £1,100.

So between 1586 and 1604, Toxteth was under the temporary ownership of Smolte and Aspinwall. After 1604, the park stayed in the Molyneux family (titled the Earls of Sefton until 1972 with the death of the 7th Earl).

Aspinwall invited the Puritans, not the Lords Derby or Molyneux

As stated earlier, it is often written that farming and milling began after Toxteth was finally disparked (circa 1590/91). Also that it was either Stanley or Molyneux who invited people of the Puritan faith to then settle on the newly cleared land.

The 1590s date may have arisen from a report made in 1604:

On the 2nd June 1604 an Inquisition was held to enquire whether a certain parcel of ground called Toxteth Park was disparked and converted into husbandry or not. The Park was inspected by Commissioners who found that the ground was disparked and that there was not one deer in any part of it, and that the ground was divided and shared unto several tenants.

The Ancient Chapel of Toxteth Park, Lawrence Hall, 1935, HSLC

Over twenty dwelling houses and two water mills occupied by various tenants had been erected and the Commissioners after diligent enquiry found that the Park had been converted to husbandry for twelve years and upwards.

It seems we can go a little further back with our date for the first Puritan settlers. William Foxe is recorded as being there in 1586 (the year Smolte and Aspinwall had taken over).

Like the other new settlers Foxe was a Puritan, these pioneers of the park were predominantly from Warrington and Ormskirk, including the Aspinwall family. Toxteth Park would provide later the Puritans with a safe haven away from increasing religious persecution under the reign of James I (reigned 1603 – 1625). This would see many Putritans leave Britain for America, including the minister of Toxteth’s chapel, Richard Mather who left for the New World in 1635.

It has been said the Liverpool was a Protestant town ran by Catholics – the two most important families in the area, the Stanleys and the Molyneuxs, were both Catholic and both subject to discrimination themselves. Why would these two famlies support the Puritans, who had fundamental differences with the Roman Catholic faith? But as we have seen, the earliest Puritan settler arrived when Smolte and Aspinwall had taken over the park. As Aspinwall was Puritan it was more likely him, and neither of the Lords, who distributed the land to people of his own faith, see here.

Smolte may have been C of E, as there is a record in the church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Ormskirk in 1570 for Emlin, daughter of Edmund Smolte:

Baptism: 16 Mar 1570/1 St Peter and St Paul, Ormskirk, Lancs.

Emlin Smolte – Daughter of Edmund Smolte

Register: Baptisms 1557 – 1626, Page 30, Entry 4

Source: LDS Film 1849663

Not just farmers, the Puritan settlers were had skilled watchmakers in their fold (Thomas Aspinwall was the earliest known watchmaker in Lancashire with two watches dated 1607, his son would move to London, employing Liverpool craftsmen).

Apart from William Foxe, Edward Aspinwall is recorded as living there before 1586. By 1597, William, Peter and Thomas Aspinwall were also at Toxteth Park:-

Edward matriculated at Brasenose College, Oxford on 23 April 1585. There was a bequest of 6s in gold to Edward Aspinwall in the will of William Foxe, gent. of Toxteth Park and Rhodes (comptroller, of Lord Derby’s household) in 1586. ‘Wm Aspenwall’ together with Peter and Thomas Aspenwall was witness to the seisin of a messuage in Toxteth Park to Edward Aspinwall in 1597.

Courtesy of Aspinwall of Aspinwall (Ormskirk) and Toxteth Park

The Puritans were inspired by their faith to rename the natural features of the landscape of their new homeland. The Otterspool stream became the River Jordan and a headland at the Dingle became David’s Throne with a cave nearby known as Adam’s Buttery.

Edward Aspinwall was co-founder of the centre of the community’s faith. By 1604 there was approximately twenty settlements in Toxteth Park. In 1611 they built a school near to a stream that led to The Dingle (Richard Mather was the first schoolmaster). In 1618 they built a chapel next to it, this still survives and known for many years known as The Ancient chapel of Toxteth.

Shown below is a beautiful memorial to Edward Aspinwall in the Ancient Chapel of Toxteth.

Image: Andrew Teebay/Liverpool Echo

The Puritans would also make their mark on an international scale in science, religion and education through Jeremiah Horrocks and the aforementioned Richard Mather. Edward Aspinwall played a huge part in the lives of both men. Aspinwall’s home was the Lower Lodge at Otterspool, said to have been one of the two Royal Hunting Lodges erected after King John took over the park. The Higher Lodge still survives (although much altered).

You can read about the royal lodges, and Mather and Horrocks here.

500 tonnes of trees cut down after the English Civil War

Although Liverpool was predominantly protestant and Parliamentary in their support, both the Stanley and Molyneux families were Catholic Royalists. In 1644, Lord Molyneux betrayed Liverpool by advising Prince Rupert how to invade the town. After a bloody slaughter, a two month-long siege began. The Molyneux’s did not just advise Prince, Rupert. Caryll, the brother of Lord Molyneux used his local knowledge to lead the bloody attack:

Prince Rupert’s men did slay almost all they met with, to the number of 360, and among others… some that had never borne arms,… yea, one poor blind man

After the defeat of the Royalists, Lord Molyneux and the other Royalist supporters were forced to make reparations to the wrecked town. In Molyneux and Derby’s case, they had to supply 500 tons of timber from their forests to help rebuild the devastated town.

Ordered that 500 Tuns of Tymber be allowed unto the Towne of Liverpoole for rebuilding the said Towne in a great pte destroyed and burnt downe by the Enemie, And that the said 500 Tuns be felled in the Grounds and Woods of James Earle of Derby, Richard Lord Mollyneux Willm Norris Robert Blundell Robt Mollyneux Charles Gerrard and Edward Scarisbricke Esqrs. And that it be referred to ye Comittee for Lancr that are members of this Howse to take ordr for the due & orderly felling the said Tymber and for apporceninge the Quanteties to be allowed to the psons yt suffered by the burninge of the said Towne for ye rebuilding thereof.

Liverpool during the Civil War, Miss E. M. Platt, 1909. HSLC

Toxteth laid bare and ripe for development

To summarize, the forest of Toxteth Park had been used for Welsh castles in the 13th century. Then had trees cleared to make way for farms for the Puritans from the 1580s. Finally many more trees were felled to rebuild Liverpool after the Civil War. By the late 1600s we can assume that little survived of the forest and not one deer was left in Toxteth Park by 1604.

Oak was also in great demand for ships of course, including the Royal Navy’s fleet during the wars of the 18th century. By the middle of the century, the availability of oak in Liverpool (and Britain in general) was in such short supply, that a warning was given in a book published in the last year of the Seven Years War (1756–1763). A Liverpool shipwright to the Royal Navy named Roger Fisher published ‘Heart of oak the British bulwark. Shewing, Reasons for paying greater attention to the propagation of oak timber.’ Fisher warns that the forests from Liverpool, along the Welsh coast to Caernarvonshire, had been ‘much exhausted’.

It wasn’t just the Royal Navy who were desperate for oak to build ships. Liverpool slave merchants such as Joseph Manesty would be forced to get their some of their ships built in America instead.

Sir, I desire you will order Two vessels built with the best white Oak Timber at Rhode Island, both to be Square stern’d with 2½ and 3 Inch plank with good substantial bends or Whales, they are for the Affrican Trade to have middling bottoms to have a full Harpin and to carry their Bodies well forward and in the upper wrork not so much tumbled in as common for the more commodious stowing Negroes twixt Decks.

Letter from Joseph Manesty to John Bannister of Rhode Island, 1745

With much of Toxteth cleared, the area was then suitable for development. The first step Earl Sefton needed was permission to build, this came from an Act of Parliament in 1772 (see next section). But the progess to populate Toxteth Park was slow. But over 100 years after the Act, the park would gradually start disappearing under a network of terraced streets.

Toxteth Park begins to be developed

From 1771 the first area of Toxteth Park to be developed was ‘Harrington‘ through an Act of Parliament from Earl Sefton (Molyneux). Parliament Street was named to honour the fact. The area was named after Earl of Harrington – the father of Isabella Stanhope, the Countess of Sefton.

Cuthbert Brisbrown was commissioned to develop Harrington. The first land to be developed was the farm of Thomas Turner. Brisbrown also built, and probably designed St. James’ Church (1774–75). Brisbrown faced financial difficulties because American War of Independence and was bankrupt in 1777.

Industry too had moved to the park, with shipbuilding on the shore and copper works – later the Herculaneum Pottery works. Although part of the park had become densely populated with insanitary court housing, most of the park remained rural.

Wealthy merchants chose Toxteth Park as the ideal location to build their mansions – moving away from the increasingly overcrowded town. Farm land was sold off to accommodate these villas, being just a couple of miles from the town and with splendid views of the Mersey and Cheshire shore. Two of the earliest sites picked for development were St. Michael’s Hamlet and Lark Lane.

19th century

Maps up the late 19th century show the sharp contrast between the developed north of Toxteth Park and the south, which until terraced housing arrived was still farm land and merchant villas often with with gardens so large they lead to the shore of the Mersey.

The building of the much-needed terraced houses on Aigburth Road started by St Michaels Road and slowly but surely crept towards the Dingle, gradually eradicating most of the old park. Thankfully the Ancient Chapel was spared. Public parks helped retain some of the character of the landscape; Princes Park (opened 1842) and Sefton Park (opened 1872).

Rediscovering the ancient boundaries of Toxteth Park

The exact borders of Toxteth Park prior to King John (or indeed until the mid 18th century) are not known, but several historians have attempted to discover them (we’ll come to them later).

We know for sure that the southern border of the park terminated at Otterspool. The eastern border would have been where Smithdown Road was later laid out. The western border was of course the Mersey, but the border closest to Liverpool appears to be of a much later date.

An examination of the boundaries on Yates & Perry’s map of 1769 shows that all the boundaries, apart from the north, followed the natural course of the land, formed by the Mersey on the west, streams and land plots on the south, and on the east where the edge of the forest once terminated (later Smithdown Road).

The north boundary closest to town is clearly artificial. Rather than following geographical features, it is almost a straight line, cutting eight fields in half in the process. Therefore the field divisions are likely to be older than the boundary. The boundary is coloured red below.

The northern boundary (Parliament Street and Upper Parliament Street) is likely to be considerably later. Parliament Street was named after an Act of Parliament in 1772 when Earl Sefton was granted permission to develop part of his park to create the area known as Harrington. The development of Upper Parliament Street is much later, Gage’s map of 1836 shows the street laid out but little or no buildings erected on it.

The straight north boundary appears two hundred year earlier in a description from 1571, the Park Wall is described as running from Hollin Hedge (after the Moss Lake) down to Booth Mill at the edge of the Mersey.

From the Water Street End to the Beecon Gutter on the north side of Liverpoole, thence to the Grove and the Meer Stone in Mr. Moore’s Meadow, thence of Kirkdale Lane to the Meer Stone there over against the Beacon, thence to a Meer Stone in Syer’s ditch adjoining to the breck, thence through the field (that is the Town field), thence through several Closes to a Meer Stone upon Everton Causeway, thence through several fields to Liverpoole Common, and so after the Common side to the Meer Stone at Johnson’s field end on the East side of the Town, and so up the gutter or Valley to the Moss Lake to a place called Hollin Hedge, and thence straight to the Park Wall and through two Crofts to Booth Mill, and so to the sea side and all along the sea side over the Pool and thence along the sea side to Water Street end.

Selections from the Municipal Archives, Volume 1, Picton, 1883

The Great Heath and Moss Lake

The map below appeared in Ramsay Muir’s History of Liverpool (1907). It is an attempt to recreate the area in the 14th century, yet the cartographer has made no attempt to establish an early boundary of Toxteth Park, instead it shows the boundary as it was known in the 16th and 18th century.

The area between Liverpool and Toxteth Park is an unoccupied expanse, with the ‘Moss Lake’ at the top and the ‘Great Heath’ at the bottom. Between these is a water course that was known as the Fall Well. Muir described the area beyond the village Liverpool:-

Behind the village and its fields, our imaginary explorer would see a long ridge of hill, varying in height from one to two hundred feet, and probably covered for the most part with heather and gorse.

At one point on this ridge, a little to the north-east of our hamlet, there lay another ‘berewick,’ that of Everton ; further south again a level stretch of ground, half way up the hill and covering the ground between the modern Hope Street and Crown Street, was occupied by a marsh, later known as the Moss Lake. It was overlooked by a rocky knoll, the Brown-low, or hill, where the University now stands.

And past the Brown-low a little stream ran down the hill from the Moss Lake, emptying itself into the Pool near the bottom of the modern William Brown Street.

A history of Liverpool, Ramsay Muir, 1907

Another watercourse ran northwards from the Moss Lake, this powered a water mill that was in existence from at least the 13th century, named Eastham Mill.

A reservoir was erected on the Moss Lake in the mid 18th century, and the Moss Lake was drained. This led to the demise of the brook, and eventually enabled the land to built upon.

I will return to this brook and Eastham mill later in the post.

Abercromby Square

Abercomby Square was one of the developments erected on the Moss Lake. John Foster Senior first submitted plans for the square in November 1800. The roads are shown on Horwood’s plan of 1803, but no sign of any houses. The delay was caused by the unsuitability of the land for building. In 1816, when the plans were halted to await draining by John Rennie.

Even nine years later, the gardens of Abercromby Square were described in a newspaper article as being so waterlogged they were still ‘totally useless to the neighbourhood’:-

The walks in the garden of Abercrombie-square, which, from being completely covered with moss, have been long totally useless to the neighbourhood, except in the hottest part of the year, have been ordered to be put into a proper state.

Albion, Monday 8th January, 1827

The first houses did not appear on a map until Swire’s map of 1824. It wouldn’t be until 1837 that the houses were almost complete.

A newspaper article from 1845 describes the problems the builders faced. Three (four storey) houses had collasped as they were being erected in Upper Canning Street. Although the cause was said to be the poor quailty of the cellar walls, the article stated that the site was formerly on the Moss-lake Field. The unbroken land is the area was ‘a black moss to the depth of two to three feet”. Below that was a ‘statum of soft sand-stone’.

A stone bridge was laid over the Moss Lake brook where Oxford Street joined Grove Street:

Just where Oxford street is now intersected by Grove-street, the brook opened out into a large pond, which was divided into two by a bridge and road communicating between the meadows on each side. The bridge was of stone of about four feet span, and rose above the meadow level. The sides of the approach were protected by wooden railings, and a low parapet went across the bridge. Over the stone bridge the road was carried when connection was opened to Edge-hill from Mount Pleasant, and Oxford-street was laid out. When the road was planned both sides of it were open fields and pastures.

Recollections of Old Liverpool, James Stonehouse, 1863

A painting of this culvert is shown below, it is dated the same year Stonehouse wrote that description:

The location is shown below on this aerial view from Google maps. Abercromby Square can be seen to the left of the junction.

A long running dispute over rights to the Moss Lake

Ownership of the Moss Lake was disputed in the 17th Century when both Edward Moore (a prominent landowner of Liverpool) and Lord Molyneux (who owned Toxteth Park) both laid claim to it. Looking at the history of the area, it’s not surprising that they argued.

The Moss Lake had been granted to Liverpool in 1309 by Earl Thomas of Lancaster:-

In 1309, during a visit to the Castle, Earl Thomas granted to the burgesses for ever twelve acres of peat in the Moss-lake, at a rent of one penny per annum. This was the first piece of property ever owned by the burgesses as a body, and may be called the beginning of the corporate estate of Liverpool. The land thus granted seems to have lain near the top of Brownlow Hill. It supplied the burgesses with peat for their fires, which they had previously been in the habit of digging in Toxteth Park.

A history of Liverpool, Ramsay Muir, 1907

A pipe roll made during this time (the reign of Edward II, 1307 – 1327) describes the divers, manors, lands and tenements of the Earl of Lancaster and Robert de Holland. It specifies the herbage of Toxteth Park as belonging to the castle of Liverpool. (See Edward Baines p. 191).

In 1357 the fee-farm lease was granted by Henry the first Duke of Lancaster. The deed mentions “the parcels of Turbary under our park of Toxteth.”

In 1393 John of Gaunt leased to Liverpool the Common pasture between the town and Toxteth Park. When this lease expired, the town continued to control the area uncontested:

Then came John of Gaunt’s lease of 1393 to the town of the common pasture lying between the town and the Park of Toxteth, which gave the burgesses a definite, if temporary, control in regard to what had hitherto been a matter of customary right; and the town thus got a grip over the wastes and commons of the township which was never relinquished. The lease no doubt expired in due course, but the town quietly continued to control the commons, and no one seems to have been sufficiently interested to interfere.

The Townfield of Liverpool, 1207-1807, R. Stewart-Brown, 1914, HSLC

The Corporation is also recorded as acquiring the Great Heath (below the Moss Lake Fields), from Moylneux in 1672:-

From the early part of the 18th Century the bulk of the town’s property consisted of the Mosslake Fields, granted by Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, in 1309, and of the Great Heath, wrested from the Molyneux family in 1672 by the courage and perseverance of the Corporation. This extensive area, extending from Islington to Parliament Street from North to South, and between Whitechapel and Crown Street from East to West, constitutes the present Corporate Estate, portions of which have at different times been conveyed freehold, but of which the great bulk is leased for terms of 75 years, the fines for the renewal of which produce a large revenue.

Municipal archives and records, from A. D. 1700 to the passing of the municipal reform act, 1835, Picton

Liverpool had control of ‘six acres of Moss’, but the rest of Moss Lake Fields did not belong to the town (p. 53). The town had also acquired parts of the Great Heath, this had tenants with free-holdings.

The Moss didn’t have any tenants until the early 1800s (Picton). The Heath on the other hand was ‘held in socage’ (a feudal tenure of land involving payment of rent or other non-military service to a superior) and the town ‘considered’ the Heath its own.

Moore Vs Molyneux

Edward Moore, wrote a list of his extensive property portfolio in the 1660s. Moore claimed that the Moss was within the liberties of Liverpool, but had belonged to him and his ancestors for hundreds of Years. Lord Molyneux, on the other hand, had erected two water mills in his Toxteth Park. Molyneux had also erected dams on the Moss, insisting the land was his.

As we have seen, the truth was that Liverpool had been given access to the Moss since 1309, then repeatedly until 1393. But failures to renew this lease would be the cause of the Moore and Molyneux argument:-

Remember one other thing of great concernment : within the memory of man, the Lord Mullinex hath erected two water mills in Toxteth park, and raised dams for them within his said park ; and since these late wars, hath laid the water over and upon the moss or turf room belonging to me and my ancestors for many hundreds of years, which moss lies within the liberties of Liverpool ; but the times growing peaceable, and I intending to get a dig for turfs, as all my ancestors have done, I could not get the said turf by reason the Lord Mullinex caused his millers to lay their dams upon my moss in a great height; whereupon I caused one (blank) to scour an old ditch, over which there is a great stone plate, that hath for many hundreds of years been the usual water-course to take the waters off my firing ; and when they had opened the old water-course, the Lord Mullinex sent me a threatening letter, how Liverpool heath was all his, and this ditch was made upon the heath, and he would command his tenants in Toxteth park to come and put it all in again.

The Moore Rental, Sir Edward Moore (1634 – 1678), 1847

Note: It may have been these dams erected by Molyneux that formed Mather’s Dam. Diverting this water may have also been the reason the Dingle stream dried up.

Using 700 year old descriptions to determine the original boundaries

To rediscover the ancient boundaries, the earliest evidence can be found two places:

1. The ‘Perambulation of Forest’ that was completed in 1228, during the reign of Henry III.

2. A grant of Turbary made to the burgesses by Thomas, the second Earl of Lancaster, 1309 (3rd Edward II.)

Both these documents mention ancient place names that have long since disappeared. Several historians have attempted to decipher them in the hope that the original boundary of Toxteth Park could be discovered, but none succeeded completely.

By re-examining the previous research into these two archives, I believe we can now locate the original boundaries, and it is quite surprising.

A perambulation of Toxteth Park in 1228

Perambulation: The act of walking around, surveying land, or touring. In English law, its historical meaning is to establish the bounds of a municipality by walking around it.

In 1225 a perambulation of the King’s forests was ordered. Twelve knights took out to mark the bounds of each of the forests:

In each county with a royal forest there shall be chosen twelve knights to keep the venison and vert and four knights for agisting the woods and collecting pannage.

THE ROYAL FORESTS OF MEDIEVAL ENGLAND, Edwrad Peters, 1979

These knights included Thomas de Bethum, William de Tatham, Adam de Coupynwra, Gilbert de Kellet, Grymbald de Ellale and Adam de Molyneux.

The result of the survey (presented in 1228) was that huge areas of forest would be cut down in Lancashire. Among the forests that escaped the axe were Toxteth and Croxteth:-

That the whole shire of Lancaster ought to be disforested except the woods of Quernmore, Couet, and Blesedale, Fulwode, Toxstath, Wood of Derby, Burton Wode and Croxstath.

History of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancaster, Edward Baines, 1836

The survey marked the boundaries of each park including Toxteth, the problem for historians is that some of the place-names the knights mentioned are now lost to history, but enough clues exist for us to suggest where these were.

The perambulation is reminiscent of a later tradition of marking the boundaries of the town known as ‘Riding the liberties’. This was continued up to 1835. See Miscellaneous notes.

Two transcribed versions of the perambulation survey survived, one in the Testa de Neville and the other in the Coucher Book of Whalley. The two accounts of Toxteth Park are slightly different. As can be expected for the time, they use different spellings for some of the places mentioned. The discrepancies are no doubt the result of Anglo-Saxon place-names being transcribed by Norman knights, then copied into Latin by monks – and then translated back into modern English!

The main difference between the two versions, and one that has caused debate with historians, is a place called both Stirpull and Otirpull. The Testa de Neville records ‘Stirpull’ and the Coucher Book records ‘Otirpull’.

Because of the similarity of Otirpull and Otterspool, some historians (Joseph Boult and Robert Griffiths to name two) have claimed they were one and the same. Other historians (J. A. Picton and Thomas Baines) had claimed that Stirpull related instead to the Pool of Liverpool (for Baines, see p. 576)

Edward Baines (the father of Thomas Baines) in his 1836 history of Lancashire includes the original Latin version of the Testa de Neville account but also translates. This calls the stream Stirpull, which had a waterfall at its head, and then descended into the Mersey:

Where Oskelesbrok falls into the Mersee, & following the course of Oskelesbrok to the park of Magewom, and from the park to Bromegge, and following Bromegge to the Brounlowe, and thence crossing to the ancient turbaries between the two meres up to Lambisthorn, descending to the Watirfall of Stirpullhead, & following Stirpull in its descent to the Mersee. Near these boundaries king John placed Smethdoun, the Esmedune of Domesday.

Sir James Allanson Picton in his ‘Memorials of Liverpool’ (1857) discussed the differences and shown both versions, here is the passage as it appears as Oterpol in the Coucher Book:

Et preter Toxstath per has diuisas, scilicet, sicut ubi Oskelesbrok cadit in Mersee, sequendo Oskelesbrok in ascendendo usque ad pratum de Magewom, et de prato usque ad Brounegge, sequendo de Brounegge usque ad Brymeclogh, et hide ex transverso usque ad veteres turbarias inter duas maras usque ad Lambesthorn, et de Lambesthorne, in descendendo usque ad Waterfall Capitis de Oterpol, sequeudo Oterpol in descendendo usque in Mersee.

Solving the argument whether Stirpull/Otirpull entered the Mersey at the Pool of Liverpool or at Otterspool, is key to defining the original boundaries of Toxteth Park.

The grant of Turbary, 1309

This record is transcribed by Picton in the municipal records of Liverpool. This is the first of two volumes that he extracted and annotated in 1883. This includes another location called Pikecroft.

Between Pikecroft and the aforementioned Lambthorn were six acres of moss. Lambthorn is described as adoining the ‘goit’ of the town of Liverpool. Goit was Old English *gote for a drain or gutter. Therefore, Pikecroft was close to Lambthorn that joined a watercourse that fed into the Pool (estuary) of Liverpool.

In the year 1309 (3rd Edward II.), a very important grant was made to the burgesses by Thomas, the second Earl of Lancaster. It runs as follows :

Know all men that we Thomas Earl of Lancaster have given and granted, and by these presents confirm to our Burgesses of our town of Lyverpole six acres of mosses, lying between the Pikecroft lands and the Lambthorn, adjoining the goit of the said town of Lyverpole, to hold and to have from us and our heirs freely for ever, paying yearly to us and our heirs a silver penny at the feast of St. John the Baptist for all service. And we, the aforesaid Thomas and our heirs, the aforesaid six acres of mosses, and the appurtenances guarantee and defend to our burgesses of Lyverpolle and their heirs for ever. In witness of this we have affixed our seal in the presence of the following witnesses. Robert de Latham, Adam de Ireland, and others. Given at Lyverpole the Thursday next after the feast of St. Mark, in the 3rd year of the reign of King Edward the son of King Edward.

This moss-land, so granted, was doubtless intended as a turbary to supply the good people of Liverpool with fuel. It now forms a very valuable portion of the corporate estate, comprising the district formerly called Mosslake Fields, and including the site of Abercromby and Falkner Squares, Bedford Street, Grove Street, &c.

Making sense of the place-names

Shown below are the place-names that are mentioned, and I have shown them in the order that they appear in the perambulation, starting at the southern border at Otterspool.

1. Oskelesbrok was the name of the stream that fed onto Otterspool, this was later named the River Jordan by Puritan settlers in the late 16th or very early 17th century.

2. Magewom (being a park situated after the Oskelesbrok/Otterpool), claimed by historians to be the area around Greenbank and Penny Lane. Greenbank was in existence well before 1755, it’s earliest appearance on a map is as St. Anlsow. The authors wonder if St Anslow may have been a cartographer’s error for Stanlow and so belonged to the monks of Stanlawe Abbey, who in the 13th century, were granted lands in the area. The granary belonging to these monks still stands. At Greenbank there is a surviving lozenge-shaped fish pond that appears on a map from 1755. In 1876 Joseph Boult wondered if this could have been an ancient ‘Fish stew’ belonging to the Knights Hospitaller (but failed to present any evidence).

3. Next comes Bromegge, this is likely to have been an area of broom (thorny shrubs) that edged the forest. Smithdown Road was once the edge of the woodland, so historians claimed Bromegge was likely to be the area around Smithdown Road.

4. Next on the knight’s list was Brounlowe, historians agree this became the area around Brownlow Hill.

5. Pikecroft was an area bordering the Moss, the possible etymology is discussed in detail later.

5. After Pikecroft was Lambisthorn or Lamb’s Thorn. This came after after the ‘ancient turbaries between the two meres‘ (mere: a place of standing water). This places it after the area known as the Moss Lake. Picton suggests this may have been the name of an old (thorn) tree. Thomas Baines suggested it was a beacon (but gave no explantion why). I suggest that it could have been an ancient sheep enclosure below Moss Lake that was lined with thorn bushes, hense ‘Lamb’s Thorn’. Further evidence for this is that the Moss had no inhabitants or livestock, but the Heath below it did and was farmed as as Fee-rental.

6. Stirpull/Otirpull

We have now reached the sticking point of the last point on the perambulation – Stirpull/Otirpull. Thomas Baines in his ‘Lancashire past and present’ says Stirpull was probably a derivative of Lirpul (the earliest name for the Pool of Liverpool). Later, Boult and Griffiths claimed this was an error and it instead stood for Otterspool.

But, as Stirpull came after Brownlow Hill, it must have been somewhere around that area, and then reached the Mersey. This would place the border of Toxtath Park much further north than the accepted boundary of Parliament Street. This location was proposed by Edward Baines in 1836 (History of the county palatine and duchy of Lancaster), Thomas Baines* in 1867 (Lancashire and Cheshire, Past and Present), Joseph Boult (Speculations on the Former Topography of Liverpool and Neighbourhood) in 1866 and Picton in 1875 (Memorials of Liverpool).

Joseph Boult wrote two papers, one in 1866, where he claimed Stirpull was the correct spelling (meaning Liverpool) and attempted to find the waterfall that descended into the Mersey near Liverpool. Then in 1876 Boult wrote another paper where he had a change of heart and claimed the correct translation was Otirpull, meaning Otterspool. He also (bafflingly) suggested this may have been the stream that fed Mather’s Dam (Stanhope Street area) (p. 179). How could a stream at Otterspool have possibly fed a dam near Stanhope Street?

In 1907 Robert Griffiths took this argument further, confidently claiming Stirpull was merely a typographic error:

Mr. Joseph Boult, in his pamphlet on the Topography of Liverpool, published in 1866, accepted Stirpull as the correct word, and often making out the Osklesbroke to be the River Jordan; the Park of Magewom to lie somewhere about Aigburth Vale and Mossley Hill; the Bromegge to skirt Allerton and Mossley Hill; the Brounlawe the Southern slope of Edgehill, he was compelled to look to Mather’s Dam, that once existed in Warwick Street, for his “Stirpull.” He was, however, never able to establish a “waterfall at the head of Stirpull.” (Otirpul is correct: Stirpull is simply a misreading.)

Pikecroft

This place-name is very important to discovering the boundaries, finding it’s location is another important key to discovering the north boundary of Toxteth Park.

Know all men that we Thomas Earl of Lancaster have given and granted, and by these presents confirm to our Burgesses of our town of Lyverpole six acres of mosses, lying between the Pikecroft lands and the Lambthorn, adjoining the goit of the said town of Lyverpole

Grant of six acres of moss from 1309

The Grant of six acres of moss from 1309 is places it before Lambthorn that joined the goit (gutter) of Liverpool, and then the Pool.

The meaning of Pike-croft

An angled plot of land?

The historians debating this subject were unable to source an origin of the place Pikecroft. I found a huge clue in a later that appeared in a paper written for The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire in 1914 by R. Stewart-Brown.

In his paper entitled ‘THE TOWNFIELD OF LIVERPOOL, 1207-1807’ Stewart-Brown refers to several areas of land called Pikes, one such is the unrelated Pikeacre.

The southern boundary of the Stutts in the eighteenth century was a strip of ground called Maidens Green. On the west lay some “lands” known, from their angles, as the Crookbutts or Crossbutts and Pikeacre“.

So ‘Crook’, Cross’ and ‘Pike’ likely refers to lands with angled boundaries.

Pike: Middle English pyke, pyk, pik (meaning sharp point)

Pike-croft therefore, is likely to have also been at an sharp-angled boundary. Later in the paper, Stewart-Brown refers to the six acres of moss and these were at the ‘the angle of the Great Heath with the boundaries of Toxteth Park‘:-

We know that 6 acres of moss, probably near the Moss Lake, which lay near the angle of the Great Heath with the boundaries of Toxteth Park and the township of West Derby, were granted to the burgesses in 1310 by Thomas of Lancaster.

A farm on a hill?

Mike Royden informed us that Pike also represents a hill, like Pikeley (or Pikelaw) Hill in Calderstones for example.

Therefore, the ‘Pikecroft lands’ were either a small farm located on an angled plot of land, or on a hill, either way they were above the six acres of moss. After it came Lambsthorn, which joined the watercourse of the Mersey.

Now we have enough clues to confidently suggest where Pikecroft was located.

By far the likeliest location of Pikecroft was near Brownlow Hill. If we return to the Yates and Perry map, we see that the junction of Brownlow Hill and Smithdown Lane took a sharp 90 degree turn, (indicated by a red dot). Just below this can be seen the Moss Lake.

Recreating the boundaries as described by historians

I can now plot the routes proposed by the historians; Boult, Griffiths and Picton on conjectural maps and compare their routes of the perambulation.

To include the full arguments proposed by the historians would take up far too much space on a blog post, instead I have included the publications in the Further Reading section.

Notes on our conjectural maps: For the purpose of the maps, I have used (one of the two) areas Chandler proposed for Esmedune as the entire area of the great Liverpool Heath and Moss. To assist navigation, Yates and Perry’s map is shown pale in the background. As the maps date before roads were constructed, the maps feature (slightly later) markers to aid navigation including the two hunting lodges called Higher and Lower Lodge and St. Mary del Key (next to the site of St. Nicholas’ church in Liverpool).

Joseph Boult’s route

The three historians were in agreement on the first stages, that it began at Otterspool then up to the Greenbank area, along then along Smithdown Road towards Brownlow Hill.

Boult stated that the location of Pikecroft was unknown, so it is omitted from the map (p. 181). Although, he should have had some ideas as he placed the two meres between Pikecroft and Lambsthorn at Abercromby Square (the site of the Moss Lake). Boult insisted the correct spelling was Otirpull (Stirpull being a typographic error) and placed it at Otterspool, but then inexplicably also suggests the steam of Mather’s Dam for the waterfall of Stirpull.

Boult’s route makes little sense, and does not allow for any last point of the journey. I included a dotted line where Boult neglected to provide any information:-

Robert Griffiths’ route

Here is Griffiths’ idea of the boundary, as he was without doubt the leading authority on the history of Toxteth Park, you’d expect it to make more sense than Boult’s. Unfortunately, that is not the case.

Griffiths insisted Otirpull was the correct spelling and placed it at Otterspool. He didn’t give any suggestions whatsoever for the last stages of the perambulation. He failed completely to provide an explanation for the northern boundary which he left at Brownlow Hill.

Griffith’s start point and end point are exactly the same, which can hardly be described as a perambulation. How Otterspool was reached after Brownlow Hill is anyone’s guess. Imagined as a 13th century Satnav instruction, it would leave the King’s knights scratching their heads at Brownlow Hill:-

Sir James Allanson Picton’s route

This is based mostly on Picton’s account, which is by far the most complete and logical. Picton’s route is almost identical to that of Thomas Baines (p. 576)

As we now have a good idea as where Pikecroft was located, and it corresponds with Picton’s route, I have also added that to the route. Picton suggested Lambsthorn was an ancient (thorn) tree and placed it ‘at the foot of the ascent’ of Brownlow Hill.

Picton placed Stirpull-head (waterfall of the Stir-pool) at ‘the gentle slope from Pembroke Place to London Road’. (p. 455)

The area between the red line and the later town boundary at Parliament Street is the area disputed by Edward Moore and Lord Molyneux, and the same area that Chandler indicated as being Esmeduna Moss much later. But why Chandler didn’t realize the significance of this is a puzzle. The conclusion is almost obvious – As King John added Esmedune to Toxteth Park, Esmedune was Toxteth Park after 1207. Therefore, Toxteth Park originally included a considerable portion of the later town of Liverpool.

After an examination of the opinions posed by the historians, combined with the new evidence available since, the most logical interpretation of the perambulation of the forest is that proposed by Picton.

Picton concluded his survey with:

I cannot see any escape from the conclusion that at the time of the perambulation and report in 1228 the portion of Liverpool south of the pool was included in the manors of Toxteth and Smethedon.

After researching all the arguments I agree. There is extremely strong evidence that most of the land south of the Pool would have originally been part of Toxteth Park and not Liverpool.

But it’s not the full story, the historians who guessed the location of Esmendune were wrong as we will discover.

Summary of Boult’s and Griffiths’ routes

Boult and Griffiths clearly never plotted their courses on a map, if they had they would have realised their routes actually made no sense. Having Otterspool as both the start and the end of perambulation meant that no explanation for the northern boundary was given. This makes the whole purpose of the knight’s perambulation futile.

Instead, both Boult and Griffith’s concentrated on the etymology of the Coucher Book’s ‘Otirpull’, making the understandable (but illogical) conclusion that it referred to Otterspool. To make this link, Boult and Griffiths had to neglect the fact that Otirpull/Stirpull was mentioned next to known areas such as Brownlow Hill and other areas that were adjacent to the Pool of Liverpool (The Heath and the Moss). They should have stuck to geography rather than eytmology.

It also has to be said that Boult’s attempts at etymolgy for Liverpool’s place names were often implausable at best, and sometimes ridiculous. He attempted to attribute some placenames to the scenes of undocumented, and almost certainly invented ancient bothgrounds. Two such examples are proposing that Whitehedge Road in Garston and Penketh on Smithdown Road (see later in the post) got their names from the scenes of battles, and Magewom was named after ‘a great crime’.

While Picton accepted the similarity between the words Stirpull and Otirpull, he also provided an etymology for the name Stir-pull and Stirpullhead (being a waterfall) ‘It is the root of stir, storm – meaning violent motion’. Otterspool did originally have a waterfall, but over 4 miles away from Brownlow Hill.

Found: A map that shows the actual boundary

Many of our posts take several years to research, this being no exception. As I was close to posting, I found another piece of evidence that not only proves that a considerable area of modern Liverpool was once Toxteth park, but also shows that in fact it extended even further! It also shows where Esmedune was actually located.

The fourth volume of a book from 1898 entitled ‘History of Corn Milling’ has a copy of a map that relates to a deed dating from 1310. The map was in the posession of Lord Derby at Knowsley Hall, and had been copied by (Charles?) Okill. The map was used to describe an area known as the ‘Liverpool Old Field’. This area had ancient two mills, Eastham (mentioned earlier) and later Townsend.

In the possession of the Corporation is a copy of a grant signed by Henry at Liverpool in April, 3 Edward II, of “six” acres of heath-land “encostaunts la quote de la ville”; the word “six” seeming to be a clerical error for “dix.” The grant of *’ ten acres” is referred to in various other deeds; and Okill, in reproducing a map of the district, has marked in the margin that the ten acres were in this part of the Old Field. Respecting the map, a copy of which appears on p. 129, he remarks, “The situation of the Old Field is shown in a plan obtained from the Earl of Derby, and now preserved at Knowsley.”

History of Corn Milling, Volume 4, Some Feudal Mills. Richard Bennet and John Elton, 1904

History of Corn Milling, Volume 4, Some Feudal Mills. Richard Bennet and John Elton, 1904

It is a very simple drawing, but its importance to the early history of Liverpool appears to have been completely overlooked. Instead of ‘Liverpool Common’ its ‘Toxteth Common’ that occupies the south side of the Pool estuary (the path of the Pool was later marked by Whitechapel and Paradise Street).

The division of Parliament Street was therefore actually made to designate the grant of land on ‘Toxteth Common’ away from ‘Toxteth Park’. This allowed Liverpool rights to the common, but the area was still within Toxteth Park. This indicates that until 1310 (at the very least), Toxteth occupied almost all of the south side of the Pool, the rest of it was shown as ‘Liverpool’s Old Field’.

The natural northern boundary of Toxteth Common is made by a brook that formed a right angle, this fed into Liverpool’s Pool:

at the Dale Street end it (the Pool) received the waters of a stream known as the Brook, which scoured and cleansed it. The source of this stream lay in a large tract of swampy land at the top of Mount Pleasant, called the Moss Lake Fields, which later formed the site of Abercromby and Falkner Squares and the numerous surrounding streets.

This stream ran across what is now Brownlow Hill to London Road, from where it crossed to Islington, then through Clare Street and Christian Street to a small natural basin, called the Dingle, in Downe Street, at the foot of Richmond Row, where it was joined by another stream issuing from the high lands of Everton. The two streams continued a course slightly to the westward of Byrom Street to Dale Street, where they entered the Pool. To the present day, despite the changed surroundings, the hollow or basin at the foot of Downe Street is still discernible.

Liverpool’s Cradle, How The “Port Extended Into What Is Now The City’s Heart. A. F. H., Liverpool Echo – Friday 09 February 1940

A forgotten place named Eastham

As shown earlier, a watercourse ran northwards from the Moss Lake. This brook powered an ancient water mill named Eastham. This water mill was located near the bottom of the Brook before it joined the stream that led to Pool. The mill was in operation from 1257 (p. 125).

A history of the mill was given in the History of corn milling. This was the first recorded mill in the Liverpool area (an earlier horse-driven mill was likely to been in the castle).

Eastham water mill, together with a nearby windmill, was mentioned in a inventory on the death of Edmund Crouchback:

1297.

History of corn milling, Richard Bennet and John Elton, 1898-1904

Inquisition on the death of Edmund Plantagenet. The town contains “two mills, one a watermill and the other a windmill, worth by the year 5 marks [£3 6s. 8d.]” ; the entire rental of the town being £,25 10s.

The north side of the Eastham Brook was the ‘Old Field’ that is shown on ‘Lord Derby’s map’. Beyond that was Everton (note ‘Road to Everton’ on the plan below).

The Brook then reached the ‘Road to Omskirk’. This was later named Byrom Street (note Mr. Byrom’s House on the plan). The brook joined the Pool stream at a T junction (the north section of the Pool is obscured by the elaborate cartouche).

The dale (or dingle), formed by the intersection of the Brook and the Pool, gave its name to Dale Street that led to it. Centuries before Perry’s plan was drawn, a bridge was positioned where Dale Street crossed the Brook, and then onto Shaw’s Brow. The original bridge would have been made of wood, but a stone replacement was ordered in 1662. (p. 188).

We can see from Perry’s plan that after passing the houses of Mr. Byrom and Mr. Hunter, the water serviced a limekiln, before finally dissapearing under the end of Dale Street where it met the Old Haymarket.